Brief summary

Here we have gathered the main points from the hero for those who want to quickly familiarize themselves with the content. The full transcript of the interview is posted below.

Started painting at age 25 — with dried insects on the windowsill. Today, he depicts balconies, courtyards, signs, and high-rise buildings of Tashkent and other cities, seeing in them the beauty and rhythm of everyday life.

He has no formal art education—he is self-taught, but believes that intuition, experience, and observation can replace an academy. His first solo exhibition took place in 2023, and now his drawings are being purchased, zines are being published, and book illustrations are coming out.

Works with the simplest materials—a pen, pencil, paper on the lap—and values the "tenacity of a line" more than academicism. He feels close to architecture—especially old, residential architecture, with laundry on the balcony and bicycles in the entranceway. Tashkent for him is a heavy but vibrant city, with a Gothic December, dusty interchanges, and unexpected islands of coziness.

He defines success as a response: when the work does not leave the viewer indifferent. If inspiration does come, it finds you at work.

Full version

Here we offer the full version of the interview for careful reading.

It all started with... insects

Stepan Brand in the area of the "House of Specialists" in Tashkent. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— If you were to describe Stepan Brand in three words, who is he?

— Artist. Foreign language teacher. Formerly a poet.

— Who instilled in you an interest in art?

- I think first and foremost, my mother. Her name is Anna Zamula, she's an artist. Mom didn't teach me how to draw, but from childhood I saw how she worked, how her friends worked. I had the chance to visit the studios of various artists, to go to exhibitions. It became a natural environment for me. And later, at 25, I became interested in drawing myself.

— Why specifically at 25?

— There was a specific moment — summer of 2014, a village. On the windowsill of the porch, dried insects had accumulated: butterflies, horseflies, some others. There was nothing to do, and I decided to draw them. That's how my first series appeared. Later there were cityscapes too, but it all started with the insects.

I was lucky to have a ballpoint pen with a thin, almost nib-like tip at hand. The insects came out prickly, as if clinging to the paper. This sensation transferred to the drawing through the tool itself. I looked at the result and thought: interesting. I should continue. So one theme began to flow into another.

Artist Stepan Brand at Tashkent City Park. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— You call yourself self-taught. Doesn't that sound offensive in the art world?

— It depends on the context. The word indeed doesn't sound very serious, but in essence, it reflects the actual state of affairs.

— How do you even learn if you're self-taught?

— I didn't have an academy, but I had people I looked up to. I think even today, an artist without formal education can learn a great deal just by being around other artists — observing, communicating, trying... It's important not to be afraid. Not to be afraid of failure, not to be afraid of looking awkward in the beginning. That's normal. Many things in art are difficult to describe as a system. It all rests on experience, intuition, freedom.

— Who inspired you at the beginning? Who supported you?

— Of course, my mom. She was always happy when I started drawing. And if we're talking about one of my first artistic impressions—in childhood, we were visiting my mom's classmate, Sasha Shcherbinin. He was showing a series of paintings about the Moscow metro.

And for the first time, I saw that familiar objects like subway cars could be not just the backdrop of life, but living, vibrant heroes of art. This defined a lot.

— Has anyone ever tried to dissuade you from pursuing creativity? After all, you are a linguist by education.

— Never. And to be honest, I don't consider myself to have left the profession. I simply stopped doing translations on a regular basis and conducting theoretical research. But my main job is still related to foreign languages: I teach English and Spanish, and sometimes I translate.

Artist - you can't escape this word anymore

— Is it possible to live solely off creativity today?

— It's possible, but not for everyone. What matters here is not just talent, but also persistence, luck, and, additionally, the ability to be your own administrator. You need to know how to organize your work, understand technical, legal, and financial matters. This takes time and energy. Not everyone wants or is able to handle that. I quite enjoy working as a teacher and drawing in my free time. When someone buys the drawings, that's also pleasant and important.

Artist Stepan Brand at Tashkent City Park. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— When did you first think: "Now I am an artist"?

— There wasn't a precise moment, perhaps. It was more a combination of two parts. The first is internal: when I look at a drawing and think it turned out well, or when right in the process I feel it's "flowing," and that brings joy. Then the thought comes: "I think I really am an artist!". And the second is external recognition. When I was offered to have my first solo exhibition — that happened last autumn — it became clear: there was no getting away from that word anymore.

If there was an exhibition, then yes, an artist.

All that remained was to overcome false modesty.

— Do you ever have doubts about what you're doing?

— Sometimes, a new topic doesn't work out. Then I go back to previous ones—and keep going. Then I try something new again—and it works better.

I draw almost every day. There have been breaks — but never longer than two weeks.

Over ten years, a lot has accumulated, and sometimes I'm surprised myself: "When did I manage to draw all this?"

— Do you need inspiration to start drawing? Or can you just sit down and begin?

— More like something in between. Inspiration is a wonderful thing, but it often comes during the process. I think Picasso said: 'Inspiration must find you working.' The main thing is to start. When your mood is good and you feel energetic, you just sit down to work—and everything flows on its own. And then inspiration catches up.

— What is the most difficult thing for you in art?

— There are two such aspects. First, technically complex things that I haven't quite mastered yet: for example, portraits, unconventional angles—things I haven't tried much so far. Second, illustration. I'm more accustomed to drawing from life, when there's an object right in front of me. But illustration is about imagination—you need to conjure images that match the text. That's more challenging for me.

— Is it possible to develop imagination? Have you tried?

— Specifically — no. There was no goal to train imagination as a skill. But recently I've been doing a bit of illustration, and it's become a bit easier. For example, I made drawings for Stas Gaivoronsky's zine — it's called "P as in Parajanov," it's a kind of phantasmagorical guide to Tbilisi. It was easier for me because I was in Tbilisi myself at the time and was drawing what I saw. And the second project — Leonid Kostyukov's book of poems "Dear Passengers." That was more difficult: the texts themselves — poetry — are harder to visualize, although I used to write poetry myself. But it was interesting, and I'm happy with the result.

— In which gallery would you dream of exhibiting?

— I'm not particularly knowledgeable about galleries, especially international ones. But the first one that comes to mind is the "Tsarskoye Selo Collection" in the city of Pushkin, near St. Petersburg. That would be awesome! And if we're talking about Tashkent, I really liked how my works were displayed at "Nukus 89" — I think the exhibition design there turned out very precise. "Ilkhom" also has a good space. But I'm answering this cautiously because I don't consider myself an expert on local exhibition venues — I might be missing a lot.

— What's the strangest advice about creativity you've ever received?

— It's hard to recall something completely strange right off the bat. Sometimes people, even good artists, say: "Oh, it would be great if you painted this thing, I can just see how you'd do it." But I don't see it! It becomes a dead end. But maybe I'll see it later. I try to pay attention to such suggestions, even if at first they don't seem like mine.

— Which artists inspire you? Have your influences changed over time?

— There are artists who have long and consistently inspired me. For example, Irina Vasilyeva from St. Petersburg. Or Ivan Sotnikov. From the older generation — Rikhard Vasm and the entire Arefiev circle. Very interesting artists! If someone is not yet familiar with their work, I highly recommend it. Among my peers — Sofia Sapozhnikova, Yulia Kartoshkina, Vigen Arakelyan, Tikhon Skrynnikov, and others. Sometimes I am inspired by friends who did not become artists themselves but have a subtle feel for and understanding of art.

— And how would you describe your style? What's most important in it?

— I try to depict what is in front of me — an object, a building, a courtyard. But I don't strive for literal representation. I handle nature quite freely: something is added, something is omitted for the needs of the drawing. On one hand, I cannot work without a reference. On the other — I allow myself to change a lot in the process. The quality of the line is important to me, in the broad sense of its ability to grab attention. It's like in the tale of Puss in Boots, where he taught his master how to call for help correctly: Help! They've killed!!! They've mur-de-e-e-ered! So, in a drawing, the line must grab the viewer and make them take a closer look.

Stepan Brand paints the "House of Specialists" in Tashkent. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— What materials are you most comfortable working with?

- The simplest ones. A simple pencil, ballpoint or gel pen - these are the foundation of almost everything I draw.

Sometimes it's even pleasant to work with an inconvenient tool: a pencil worn down to the wood can draw a line that an ordinary one never could.

I often draw while holding the paper, without a tablet, just on my lap or even on my hand, placing my fingers under the sheet on the other side — this also affects the drawing.

— Is there a style you'd like to work in but haven't tried yet?

— I'd like to try graphics in a larger format. It doesn't have to be pencil or pen—maybe dry brush, charcoal, marker. It just requires a different approach: more time, more discipline, a slightly different kind of concentration. Sometimes I try working on a large scale—something comes out, but I haven't reached a full-fledged series yet. I'd like to try, perhaps on the theme of residential buildings.

Tashkent is a palette

— Where does your interest in architecture come from?

— Architecture is inherently graphic. It already has structure, logic, rhythm—it dictates how it should be depicted. Plus, there was life experience: moving from apartment to apartment in Moscow, which sparked an interest in understanding what kinds of houses exist and how they are constructed. Sometimes a building seems to say itself: "Try to draw me." And I try.

— What kind of view from a window in Tashkent would be ideal for you?

A quiet courtyard. Or a view of the neighboring house, perhaps from a height. It's important to me that there is greenery, trees, a little air. It doesn't have to be something spectacular.

— What color is Tashkent?

— It doesn't have a single color. It's a palette — white, blue, ochre, light green. But generally, I rarely use color — it's more difficult for me, it requires greater concentration. Although there was, for example, a series of small drawings about Tashkent — about 50 pieces in colored pencils. That worked out.

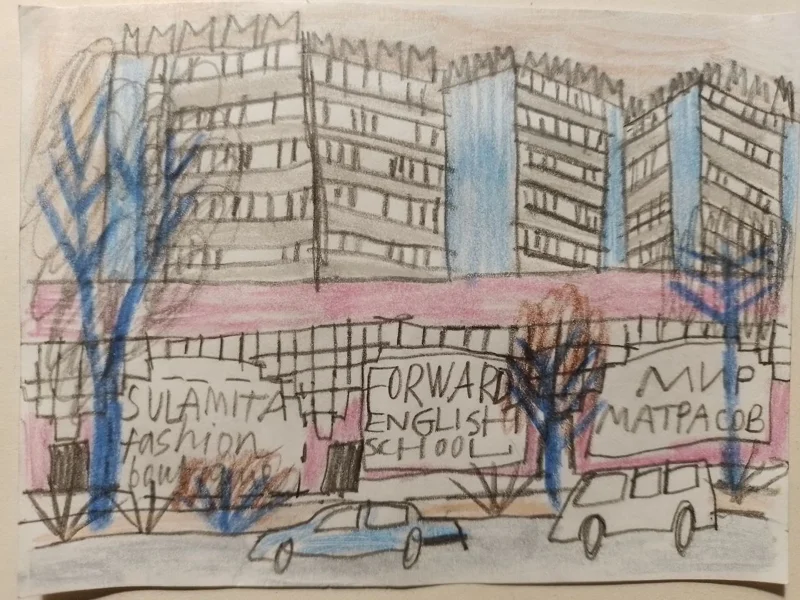

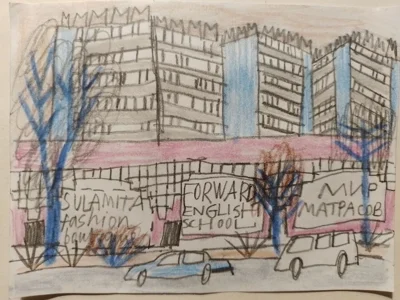

Works by Stepan Brand dedicated to Tashkent. Photo: Stepan Brand

— Which buildings are closer to you — modern residential complexes or old apartment buildings?

— Honestly, they're rather old. The Soviet-era high-rises of Tashkent are closer to my heart. Although there are some successful modern buildings—they just haven't been lived in yet.

Architecture is also about life. A bicycle on the balcony, drying laundry, a broom in the corner - all of this adds warmth.

The new houses are still too clean, sanitized. Let's see what will happen in a couple of decades.

— Do you like the mismatched glazing of balconies or are you in favor of uniformity?

— Everything depends on the building. In Brezhnev-era houses, this patchwork looks lively and fitting. In Stalin-era buildings—not always. There, it often spoils the facade. But it's not so black and white—sometimes even in a Stalin-era building, it can look interesting.

— Is there a building in Tashkent that you would absolutely refuse to draw?

— No. I would draw any. Even if I don't like a building — in graphics, it will still be different. But if I had to name what irritates me — the Central Station building. How it looks from the outside — honestly, it's disappointing.

— And which architectural objects were the most unexpected for you?

— "Pearl" — you don't have to look far here.

Lovely behemoth, an adorable colossus. Enormous, hundred-mouthed, many-eyed, and yet gentle, radiant, and humane: dwell within me, and I will soothe you.

And also, for example, the industrial zone in Mashinasozlar. There is something strange but interesting there.

Stepan Brand in the residential complex "Zhemchug" in Tashkent. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— Where do you especially enjoy being in Tashkent?

— At the Museum of Railway Technology. There's a special atmosphere there. I've been there many times, and it was genuinely good every time. I never get tired of that place.

— Trains — your favorite mode of transport?

— Yes. They are slow, measured, with their own rhythm—the clicking of wheels, station announcements, smells. On a train, you can lie down, walk around, look out the window. Unlike a minibus, bus, or even an airplane—on a train, you feel freer.

— How would you describe Tashkent: cozy or chaotic?

— It's both cozy and chaotic. But more on the heavy side. I'd even say that the opposite of coziness in Tashkent's case is not disorder, but precisely heaviness. Very wide streets, interchanges, noise, dust, construction, lack of sidewalks. That's also part of life, also interesting — both for observation and for drawing. But that's no longer about coziness.

— Have you ever been walking around the city and felt like you were in a music video? What song would be playing in your head at that moment?

— This happens more often when you're in a taxi.

Especially in late November or early December. Tashkent becomes gothic: rain, clouds, snow begins, skeletons of constructions in the darkness, neon lights. The inscription "SOMSA" in poisonous green letters. And you're rushing in a taxi along the Malaya Koltsevaya under some track like "Enjoy, Bukhara." It's a very Tashkent moment.

— What's more important in a city — the architecture or the people who live in it?

— People. Architecture is important, but people are more important. Even if the architecture is minimal, people give it meaning. They decide everything.

Stepan Brand in the area of Samarkandskaya Street. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— Can you feel the spirit of a city through its buildings?

— I think so. Tashkent has a stern spirit. I didn't expect that before arriving. You can almost read faces in the facades of Soviet buildings — they are serious, but benevolent. It's a surprising combination.

Success is the feeling of getting a return from what you do

— You move frequently. Do you already have "your" city? Or do you carry it within yourself?

— Inside, I probably still carry Moscow within me. But if we're talking about current places, right now it's Tashkent, Tbilisi, and Yerevan. In that order of significance. Tashkent is probably in first place now—or maybe on par with Tbilisi in terms of the number of drawings. I haven't lived in Yerevan yet, only visited, but perhaps if I spend some time there, there will be more works from there too.

— You create your own zines. Tell us how it works.

— It's simple. The book about Tashkent is the first and completed graphic series outside Russia. Then came the book about Tbilisi. And this winter, I made a book about Yerevan. There are three of them. I just go to a printing house or copy shop, print 10 copies from scans of pencil drawings, cut them, and bind them by hand. It's not exactly handmade—the binding is manual, but the printing is machine-made. The print run isn't limited—I reprint as needed. This rhythm suits me well.

— And with whom from the local cultural scene have you managed to become acquainted in Uzbekistan?

— I rarely visited other cities in Uzbekistan, but in Tashkent, I managed to meet many interesting people. For example, I attended collage classes by Ksenia Gorbacheva and through her, I got acquainted with her circle — talented artists and creative individuals. Among them were photographer Alexander Barkovsky, architectural activist Alexander Fedorov, multimedia artist Sofia Seithalil, and graphic artist Mikhail Sorokin. These were vibrant, inspiring encounters. In Bukhara, I was fortunate to meet photographers Behzod Boltaev and Nuriddin Juraev.

— If you had the opportunity to travel to any era, where would you go?

— I think the fifties to sixties, and maybe the seventies—they seem to me the most prosperous and somehow the right time in human history. Or during the perestroika era—probably the most vibrant and free time in the history of the post-Soviet space. I would like to be in Moscow—to see how everything was arranged, in Leningrad, and in Tashkent in the late sixties—to witness how the city was being built. Also, probably in Paris during the heyday of the Bateau-Lavoir, to meet Modigliani.

In Tashkent, I particularly wanted to witness the grandeur of the vision firsthand. Architects, designers, artists, workers—everyone who contributed their efforts to the city's creation deserves immense respect. It was a shared endeavor, the result of collective labor.

I would gladly participate in such a restoration—if the opportunity arose.

Stepan Brand at the bridge over the Burjar Canal. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— Do you have any habit that others might consider strange?

— Recently, when we were sharing fun facts about ourselves, I mentioned that I've never ordered food delivery. I either cook at home or go to a plov restaurant or a cafe. Sometimes people are surprised. And it's true, if someone asked me to order delivery now, I wouldn't know how. In that regard, my level of gadget proficiency is "grandma level."

— Do you have a talisman that you always carry with you?

— After leaving Russia, I acquired two toy houses. One is from Moscow, wooden, with a pointed roof and a slot for a postcard. But I don't put a postcard in there—it just creates a feeling of coziness. The second one is ceramic, with glaze, found later in Tashkent. If these can be called talismans in a broad sense, then they are.

— What does success mean to you?

— Success is the feeling of return from what you do. And of self-giving too.

When what you've created doesn't leave the viewer indifferent—that's already a success. Of course, there are formal manifestations too: an exhibition, the purchase or exchange of a work, a simple phrase like "I liked it"—all of that is also success. The most expensive work I've sold cost about a hundred dollars—some might say that's not much, but for me, that's also a success. Some acquaintances have said, "That's too cheap." But no one reproached me; everyone rejoiced with me.

Perhaps there is nothing particularly mysterious about success. Or maybe I just haven't encountered what is called 'great success' yet.

— What does your ideal day look like — from morning to evening?

— Preferably, get up early. What time — depends on the season, but let's say around eight o'clock. Although it doesn't always work out — that's exactly what I'd like to change in my life. To get up at eight, to manage to do something in the morning — some household chores, so as not to put them off later, not to think about them all day. Or, on the contrary — to go for a walk while it's still cool and to draw with a fresh mind. Then you won't grumble at yourself later that the day has passed and you haven't managed to do anything. It's also great to meet up with friends, to work successfully and inspirationously on the non-artistic side of things, to see something interesting, to read a book, to learn something in a new language (currently, that's Georgian and Italian).

In a perfect day, there is no rush. No disappointments. No feeling of being dissatisfied with yourself. And one more thing — it would be nice not to get stuck on social media excessively.

— What is more important to you — the process or the result?

— Both, actually. At some point, they simply converge. The process becomes the result, and the result is impossible without the process. It’s like the opposition of form and content: someone once said that content is form that has taken shape. Perhaps the result is a process that has taken form.

Stepan Brand in the "Pearl" residential complex in Tashkent. Photo: Igor Mazurkevich

— How do you know when the work is finished?

— When the lines come together well. When the composition works. Sometimes everything seems to be there, but something is missing—then I add an element of life: for example, a dog, a family with a stroller, a hot air balloon. So that a breath of life appears in the work. And it's important to stop in time—otherwise you can ruin it.

— Does the work belong to the artist after publication?

— Generally speaking, no. After publication, it departs. Although there is a moment when the work is already finished but hasn't quite separated from you yet. Over time, it moves further and further away. Although, if you take an old work, you can theoretically immerse yourself in it again and remember how and what it was.

— Have you ever wanted to redo work that was already finished?

— It has happened. For example, while preparing books: everything is already ready, you can go scan, and suddenly — you flip through, you see a couple of places where you want to add a shadow, a little person, a car. Sometimes I finish them. But to completely redo it — no. It's easier to start over.