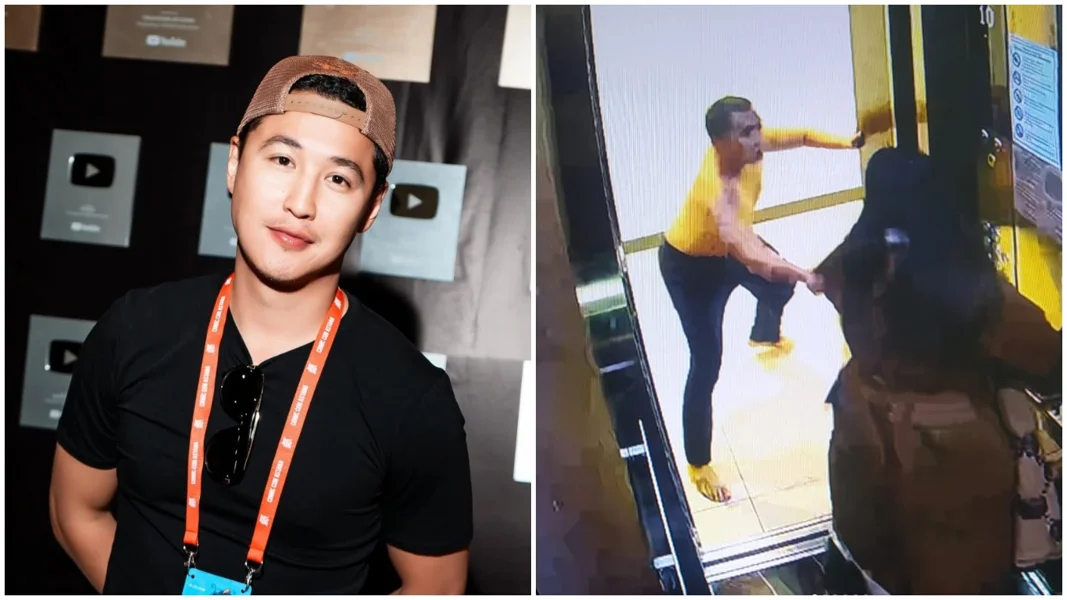

In April 2025, Kazakhstani woman Aliya Buteeva accused actor Sharip Serik, with whom she was in a relationship, of assault. Buteeva published a video on her Instagram showing a man resembling Serik forcibly dragging her out of an elevator, and also attached a selfie to the post showing visible redness. The actor, who gained fame for his roles in several Kazakhstani TV series ("Rayony", "Patsanskie istorii", "Sheker"), acknowledged that he was indeed the person in the video and apologized to Buteeva on social networks.

A public apology proved insufficient. The Almaty police has initiated an investigation, and the studio Salem Entertainment, which is handling several film projects featuring Serik, stated that it has placed him on a "blacklist" and terminated all contracts with him. "The third season of the series 'Qarga' has been canceled, and furthermore, the actor will not appear in the second season of the series 'Meow,' where he was to play one of the lead roles," according to a statement. Scenes featuring Serik will also be cut from the upcoming film "Patrol: The Last Order."

Canceling the Kazakhstani Way

The British Encyclopedia defines cancel culture as the withdrawal ("canceling") of support for people, groups, or organizations in response to actions or statements deemed unacceptable by those initiating the canceling campaign.

The emergence of the term is commonly associated with the #MeToo movement, which began in 2017 after dozens of actresses accused Harvey Weinstein of harassment and sexualized violence. Echoes of "Weinsteingate" – keeping all proportions in mind – can be detected in the scandal involving the star of Kazakh "bro" TV series.

Harvard professor Pippa Norris calls deplatforming (a synonym for cancel culture) a form of social pressure – it is exerted on those who violate ethical standards considered to be universally accepted and indisputable.

Norris believes that cancel culture manifests where the desire to ostracize those who violate these standards transforms into collective activist action.

In Kazakhstan, the issue of physical violence has become particularly sensitive following the murder of Saltanat Nukenova – in November 2023, former Minister of Economy Kuandyk Bishimbayev beat and strangled his common-law wife in one of Astana's restaurants. The investigation and trial, which were accompanied by protest actions in Kazakhstan and abroad, were actively covered by local and foreign media.

In May 2024, Bishimbayev was sentenced to 24 years in a strict-regime colony, and Nukenova's brother received compensation of 17 million tenge (over 32 thousand dollars). Whether to consider this verdict a cancellation is a debatable question. The ex-minister still remains in the public space: he is suing the prison administration, demanding a reward for winning a prison chess tournament and generating news stories.

During the process, the ex-minister (in the cage on the left) diligently turned away from the cameras © Astana Court / TengriNews

Nevertheless, both of these cases led to socially significant changes – something that some researchers call the positive side of cancel culture. If Serik's film studio is deprived of income, then the case against Bishimbayev led to the adoption of the "Saltanat Law" – a set of amendments that introduced criminal penalties for battery and intentional infliction of minor bodily harm.

Lisa Nakamura, a professor at the University of Michigan, believes that public boycotts create "a culture of accountability that is decentralized and unsystematic, but whose existence is necessary."

Where do the boundaries of cancel culture lie

Canadian journalist Connor Garel in his column for Vice writes that holding a celebrity accountable depends on the existing hierarchy, the fame of the person themselves, gender, and the quality of the apologies offered: "Celebrities rarely face a jury in the court of public opinion … cancel culture looks more like a personal story than something all-encompassing and universal."

The closest example of such a plot is the recent story involving Oxxxymiron. In March of this year, Russian journalist Nastya Krasilnikova released a podcast in which three girls spoke about grooming by the rapper. At the time of the described events, they were all between 13 and 15 years old. One of them, Victoria Kuchak from the Kostanay region of Kazakhstan, told Krasilnikova:

"He's a rapper from London and graduated from Oxford. And he's writing to me that I'm beautiful. Meanwhile, I'm sitting in an apartment with peeling wallpaper and have never left my hometown."

Despite the collected evidence (Krasilnikova assures that all the factual material was verified by at least two sources), Fedorov has not been canceled yet. Some opinion leaders supported the heroines of the podcast, others saw nothing reprehensible in what was told. Yury Dud stated that he expects explanations from Fedorov but will not stop considering him a talented artist. Some columnists insist that in the 2000s, the sexualization of teenagers was considered a socially acceptable norm.

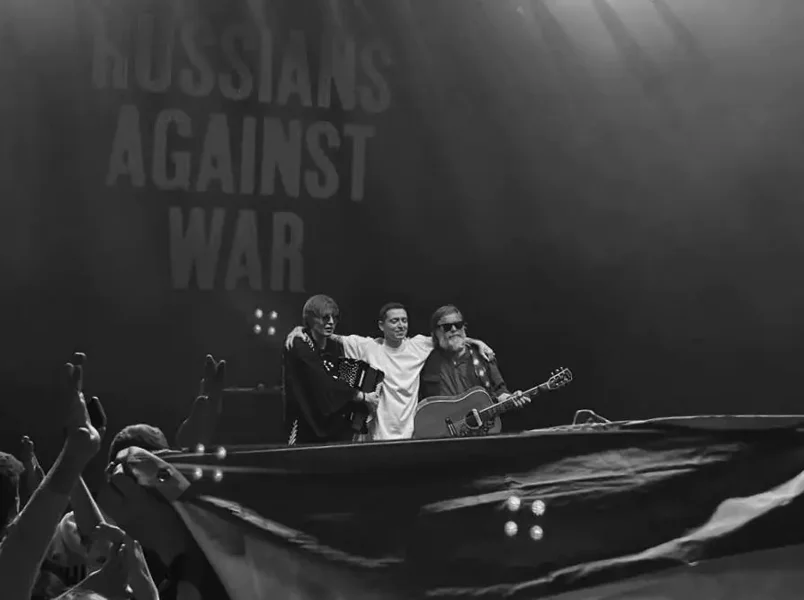

The spirit of the times matters – the peak of media attention for #MeToo and the similarly value-aligned BLM occurred in the late 2010s. Then the COVID-19 pandemic began, immediately followed by the war in Ukraine, opposition to which became a categorical moral imperative. Oxxxymiron's anti-war stance is the rock against which attempts to cancel him for alleged grooming have so far been shattered. In a sense, the rapper himself is a victim of cancellation by the state. His songs have been included by Russian authorities on the list of extremist materials, and since 2024 he has been wanted under a criminal warrant.

Zemfira, Oxxxymiron, and Boris Grebenshchikov at the Russians Against War concert in London © Zima Magazine

Who and how were canceled in Uzbekistan?

The war in Ukraine has significantly politicized cancel culture in the global information space and has influenced its recent manifestations in our country. In this case, the state becomes a subject of cancel culture—it formulates ethical standards for public figures and attempts to prevent their violation.

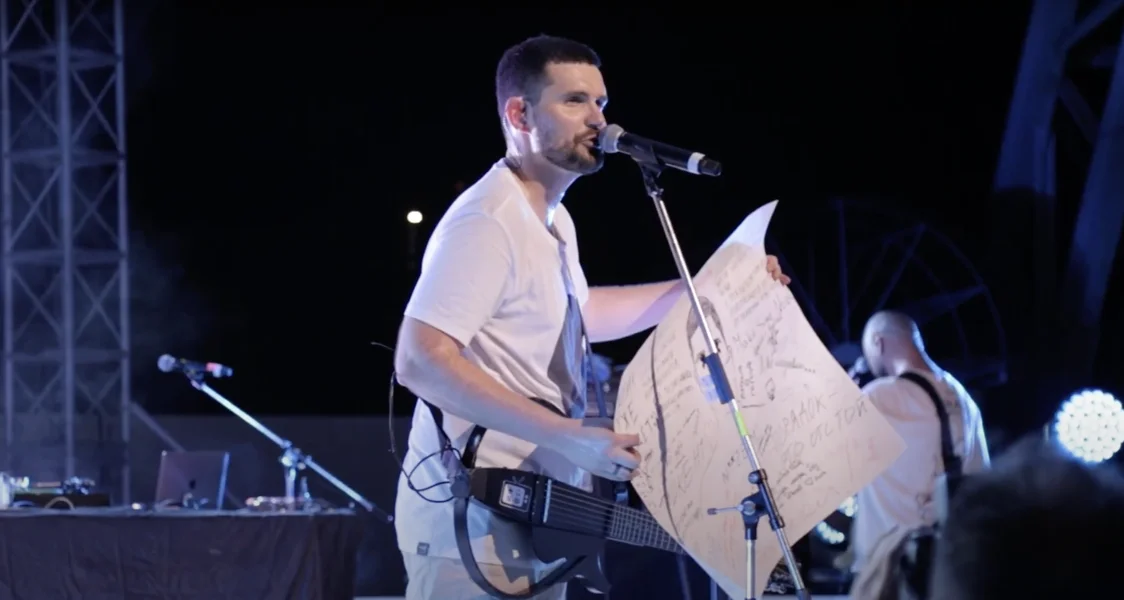

In the summer of 2022, Noize MC (Ivan Alekseev), an icon of Russian rap-rock, performed at the summer venue of the "Turkiston" Palace. During the concert, he delivered an emotional anti-war speech, which the audience supported with pacifist chants. Apparently, Noize MC's performance became a trigger for the depoliticization of the cultural scene.

In 2023, at the last moment, the performance of the Russian indie-pop band SBPC at the "Groza" festival was canceled - the participants wished the organizers strength and added: "And we wish nothing to the authorities." Subsequently, the lineup festival "WeCosmos" was canceled, just a few days before it was set to begin.

Screenshot of the recording of the first and possibly last Noise concert in Tashkent © Afisha.uz / YouTube

In April of the same year, the documentary film festival "Artdocfest/Asia" was disrupted in Tashkent. Its program included the film "Eastern Front" about Ukrainian volunteers evacuating the wounded from the front lines – film critics called it the strongest film at the Berlinale. The Ministry of Culture of Uzbekistan cited a procedural violation: the organizers did not obtain permission from the Cinematography Agency for a public screening and did not notify the Ministry of Internal Affairs about the event.

Meanwhile, the pendulum of cancellations swung in different directions. In May 2023, bloggers and online activists managed to get the cancellation of the "Zhara" festival in Tashkent – its co-founder was Grigory Leps. The artist tours the occupied territories of Ukraine and actively supports the war, including financially: he paid bonuses to Russian soldiers for destroyed Ukrainian tanks. Following "Zhara," Leps's solo concert, which was scheduled to take place in the capital in October of the same year, was also canceled "for technical reasons."

In this case, apoliticism acts as a space of safety, and deplatforming occurs in the form of administrative intervention.

"Russian artists have come to us not for the first time, they come every year, we acknowledge that they have fans in Uzbekistan. But we will not allow them to express their political position," said Minister of Culture and Tourism Ozodbek Nazarbekov in 2023.

Invisible pants, moral panic, and canceling the cancellers

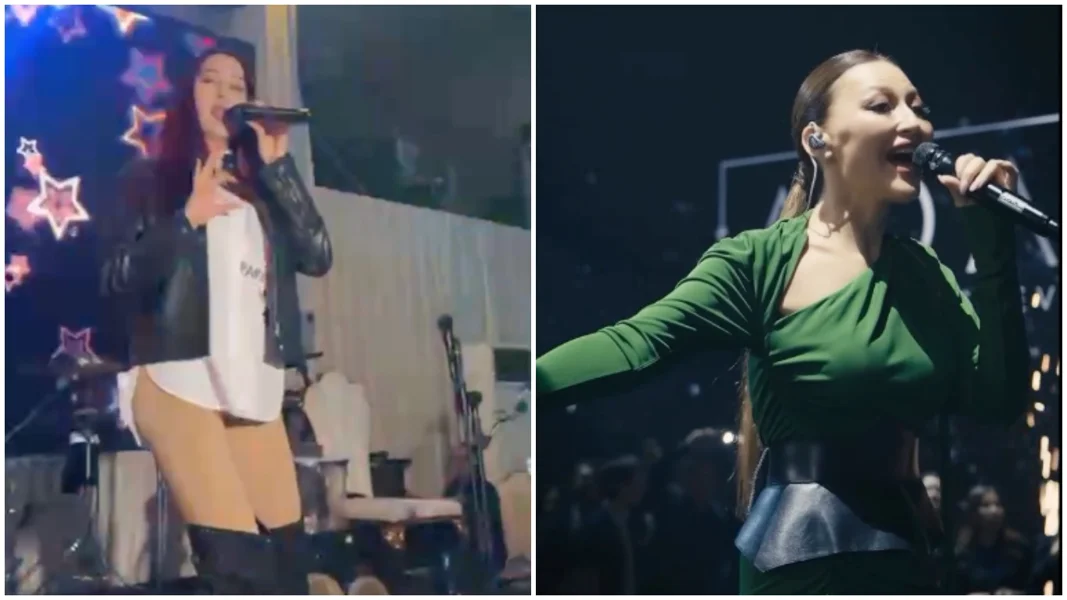

Politics is not the only "double solid line". Two years ago, singer Kaniza (Shakhrizoda Akhmedova) was deprived of her license for a month after performing at a wedding in nude-colored trousers. Some online activists could not see them in the video and believed she performed without them at all. "Uzbekconcert" instructed Kaniza to "get back in line" and threatened consequences. The singer did not remain in debt and stated that someday the officials of "Uzbekconcert" themselves would be canceled.

Last year, the concert agency summoned popular singer Lola Yuldasheva for a conversation. A video of her performance spread on social networks — some users considered that her emerald-colored stage outfit too clearly emphasized the star's figure. However, the clip was edited — it was cut from an old recording and the sharpness was enhanced. At "Uzbekconcert," Yuldasheva was informed that they had no claims against her, but wanted to officially document the summons to the carpet to protect her from harassment.

Not only artists have faced attempts at cancellation, but also advertising posters. In Tashkent, a storefront of the Belarusian lingerie brand Milavitsa was filmed by an outraged local resident. The author called the models showcasing the brand's products "prostitutes" and urged authorities to protect children from adult content. The store replaced the advertisement with a more modest one, but the activist himself also suffered. On social media, he was called a "Taliban fan," and law enforcement imposed a fine on him for the illegal distribution of religious materials.

Russian culturologist Alexander Mannin explains moralizing cancel culture from the perspective of social psychology. He writes that cancel culture, which carries a strong activist charge, looks different where there is no space for constructive public dialogue. "We want action, we want to feel that we can do something. But we do not want to discuss why this is happening, and there is no platform or environment for it; it's not the time for reflection. We must act."

Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Anne Applebaum sees in cancel culture a "new Puritanism" and finds within it manifestations of moral panic. Mannin agrees with her:

Anti-Semitism in Europe, Germanophobia with the onset of World War I and after World War II, Islamophobia after 9/11 — these are very different social and cultural phenomena, yet they have something in common. All these processes are fundamentally based on the fear of the Other, the fear of the Different, and aim at preemptive protection against it.