Brief summary

Here we have gathered the key points from the heroine's story for those who want to quickly get acquainted with the content. The full interview transcript is posted below.

The Andakulova Gallery became the first platform in Dubai specializing in contemporary art from Central Asia, and over 13 years has transformed into a hub for artists, collectors, and researchers. Its approach is based on systematicity, a pedagogical foundation, and a desire to make art alive and accessible. Support for young artists, participation in international fairs, and publishing projects are all built around the idea of creating a sustainable reputation for the region in the global art context. Emphasis on professional education, visual literacy, and digital presence are essential conditions for success. It is important for students and young artists to understand the structure of the art market from the very beginning, to compile portfolios, participate in open calls, and be visible in the digital environment. Collectors can be cultivated through lectures and dialogue, and art is not a luxury, but a way to live surrounded by meaning.

Full version

Here we provide the full version of the interview for careful reading.

The Path to Art from Formulas to Gallery

— This year, your Andakulova Gallery is turning 13 years old—a considerable journey, especially in such a complex field as gallery management. Let me start with the main question: in your opinion, what kind of education should a professional gallerist have? What is important for those who dream of connecting their life with art and its management to know?

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

A gallerist is a jack-of-all-trades: they run a business, build relationships with artists and collectors, track trends, have an ethical sense, and analyze the market.

It's important to have an art history education — it's the foundation. Today, fields like art management and art business are developing; they provide an understanding of how the market is structured and how the system works.

I also completed a six-month Professional Management Program (PMP) at the Uzbek-Japanese Center — this provided valuable practical skills, especially at the start: how to begin, avoid mistakes, and build a structure.

— There's a sense that you're a person who never stops learning. Your first degree was in physics and mathematics. How useful has it proven to be in the field you now live and breathe—art?

— I am certain: any education is valuable. Mathematics did not come easily to me, but seven years at the Pedagogical University of Navoi became my foundation. I can do mental arithmetic quickly—it helps in business, as does mathematical logic.

The most important aspect is the pedagogical foundation: philosophy, methodology, teaching fundamentals. This knowledge proved invaluable when I started leading educational courses. We teach storytelling and how to make art lively and interesting for the viewer.

Today I continue my studies — currently in a master's program at the Kamoliddin Behzod National Institute of Arts and Design. Previously, I completed a distance learning bachelor's degree in the "Theory and History of Art and Architecture" department at the Ilya Repin St. Petersburg Academy of Arts.

— A mentor is important in any journey. Who was yours?

— My mentors became Nigora Akhmedova and Babur Ismailov.Nigora Rakhimovna supported me at the moment of the gallery's opening and insisted on my enrollment in the master's program in St. Petersburg, and her advice is very important to me.

Babur introduced me to artists, generously sharing his knowledge, time, and ideas. He opened up the professional community for me — and that is truly valuable.

First step, support, mistakes, and confidence

— Why specifically a gallery? Not a restaurant, not some other business space?

— When I told my friend about the gallery, she was surprised: "You'd be better off opening a taxi company—art isn't a business." But I already knew exactly what I didn't want to do. I didn't want to work "at a job I hated"—I've always loved to draw.

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

I studied under Hakim Karimovich Mirzaakhmedov, and on weekends, I attended art history lectures by his wife, Tatyana. These meetings were inspiring, and I felt I was in my place.

But to seriously pursue painting means having time. And combining being an artist and a gallerist is almost impossible.

— Why did Dubai become the place where you opened a gallery?

— It was a coincidence, but a very fortunate one. In 2012, there were almost no galleries in Dubai, and today it's a world-class art hub: museums, fairs. Art has become part of the Emirates' cultural strategy—and I'm glad I was among the first.

Opening the gallery was an expensive decision—I took out a loan and literally "worked to pay it off." The space is small, 60 sq.m, and I still don't know if the gallery has paid for itself. Fortunately, my husband supports me. Art rarely brings stable profit—more often, money goes toward organizing exhibitions, publishing catalogs and books. It's a constant cycle of investment.

— How did the opening go?

— We opened with an exhibition by the artist Timur D'Vatz. He's a very interesting figure: he was born in Moscow, studied in Tashkent, and then graduated from the Royal Academy of Arts in London — the first Russian-speaking graduate of this university. We are very proud that his exhibition was our first.

Timur D'Vatz's works. Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— What mistakes did you make at the start that you now view differently?

— You know, I wouldn't call them mistakes — it was a path. I was 29 when I decided to open a gallery, and honestly, I had little idea how everything worked in practice. Everything happened through trial and error. And yes, I can still make mistakes somewhere — and that's normal. Every project, even if it didn't succeed, is an experience. It doesn't disappear anywhere but becomes a part of professional growth.

— And competition? It existed too, I suppose?

— Of course, competition always exists. But in Dubai, it's a different culture—more of a healthy competition, without aggression. Galleries there know how to collaborate: they organize joint events, support each other. I think art in general is moving towards cooperation, dialogue. As an art historian, I give lectures not only in my own gallery but also in other spaces.

We had a whole series of lectures on the culture of Central Asia, South Asia, on the contemporary art of Iran, Japan, China, and the Middle East. Because these are entire artistic worlds. And to truly understand the present, it's important to look broader, to see the interconnections.

— Does a 'glass ceiling' exist for women from the East in the art world?

— You know, in the UAE, it's the opposite. Here, oddly enough, women are given the green light. People strive to help and support them. A female entrepreneur commands respect. Here, they don't hold you back but rather inspire you—especially if you work professionally and with passion.

Criteria, prices, trust, and the start of young artists

— Does your gallery host exhibitions not only by painters?

— Of course. We have exhibited sculptors, photographers. We have organized both solo and group exhibitions. For example, a project with female artists from Kazakhstan — six women participated in it. The themes of the exhibitions can be very diverse — from the national code to experiments with form.

— How do you determine if an exhibition was successful?

— It's hard to measure. Sometimes it's enough for ten people to come, but one of them remembers, gets inspired, wants to come back. Success is not always about scale, sometimes it's about the depth of impact.

— At what point did artists themselves start taking the initiative to exhibit with you?

— About three years after opening. From the very beginning, we tried to build honest, trusting relationships — and gradually artists started approaching us on their own. Almost everyone we work with proposed collaboration themselves.

– Do you have your own criteria when selecting artists?

— Yes. An artist must have professional training. It is immediately apparent whether a person has command of composition, a sense of color, and the ability to construct form. I believe an artist should have a higher art education. Without a foundation, it is very difficult to speak of a profound and technically precise statement.

— Who determines the price of a work of art? Is there a commission in the world that handles this?

— There is no single commission, but the company Art Vernissage has started systematically addressing this issue. They are developing a system for evaluating artists and their works. This is very important, as pricing is a complex and multi-layered process.

— And what do they base the final price on?

— The price depends on many factors: the artist's age, education, status, demand. One can be famous, but if the works aren't selling — the price is too high. Young artists often overestimate themselves. The art market exists precisely to establish this balance.

If works are selling, the price is right. If not, it's worth reconsidering. Art doesn't have to be expensive, but it should be realistically valued. Today, works by Uzbek artists are still investment-attractive — prices are moderate compared to the global market.

— Were there any artists for whom your gallery served as a launching point?

— Yes, of course. One example is the path of Dilyara Kaipova. In 2016, we organized an art residency in Abu Dhabi. Five artists participated, and Dilyara was among them. After this residency, there was a shift in her work: it became more restrained, mature, and focused on working with textiles and identity.

Since then, her works have been exhibited at biennales, and over the past five years, 13 museums have acquired her pieces. This includes the legendary Victoria and Albert Museum in London.

— How are relationships with young artists built?

— At first, students tend to be a bit passive. But gradually it dawns on them that the information I provide is primarily for their own benefit—it's an investment in their future, not just my time. That's when engagement emerges. It's not easy to hold attention these days: we live in the age of Instagram, everything is fast, fragmented, attention is scattered.

Now, fortunately, the times are favorable. The economy is more stable, interest in interior design and art is growing — and young artists are getting more and more opportunities. New spaces demand a new perspective, new meanings. Landscapes and still lifes no longer always meet the demand — people want a different language. And if a young artist senses the trend, offers an original product, and sets a competent price, they have every chance to succeed.

— What advice do you usually give to young artists who want to advance?

— Today's young artists are very advanced. They understand both marketing and social media. I taught an art marketing course at Tashkent International University KIMYO for graduating students of the art faculty. We examined how the art market works, how to build a strategy, how to manage social media — because today it's impossible without that.

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— What is your attitude towards the common opinion that "you can't make money from art," and that a true artist must be poor?

— I disagree. If you have talent, diligence, and the ability to present yourself, opportunities will be found. A portfolio, a structured CV, and participation in residencies and open calls help.

I always say: make it convenient for the gallery owner. If an email lacks a catalog of paintings with titles, sizes, and prices—it gets lost. Everyone is busy, and an artist often only has one chance.

Today, digital presence is what matters. Instagram, YouTube, search engines—these are already part of a professional image. If an artist has no online presence, trust diminishes. Conversely, interviews, videos, and behind-the-scenes work generate interest.

— Have your students applied to participate in global exhibitions?

— Yes, when my students applied for reGeneration – Emerging Photography from the 21st Century, many said it felt like filling out visa documents. Everything is precise: deadlines, formats, list of required files. It's both stressful and a sign of a high standard. The competition itself is perceived as a full-fledged career stage, almost like participating in a residency.

Today information flows continuously, and you have one chance — one email, one email, one portfolio, one Instagram page. And this first impression must be strong, vivid, precise. An artist today is not only a creator but also a manager of their own reputation.

Central Asia on the World Art Map

— Does your gallery exclusively represent artists from Central Asia?

— Yes, the main focus is Central Asian art. But once a year we rent a gallery to give young artists an opportunity to showcase their work, or we organize collaborations. But overall, we adhere to one clear direction.

— Have many artists from Uzbekistan and Central Asia already exhibited in your gallery?

— We should sit down and calculate! Because besides the exhibitions in the gallery space, we regularly participate in international art fairs — and that is also part of our work. Among them are Contemporary Istanbul, Abu Dhabi Art Fair and London Art Fair. We take our artists abroad, represent Central Asia, and participate in a dialogue with the global art community. All of this requires serious preparation and resources, but yields a tremendous return.

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— How high is the interest in the region's art?

— Central Asia is a true treasure trove. We have the strongest academic school. Artists from the 60s and 70s received a serious education: many graduated from the Ilya Repin St. Petersburg State Academic Institute of Fine Arts, Sculpture and Architecture or the Surikov Moscow State Academic Art Institute. This formed a solid professional foundation.

Add to this our cultural heritage: applied arts, ancient architecture, traditions, a unique visual language. And also the historical intersection of cultures—Persian, Chinese, Indian, Greco-Bactrian. Here, one can endlessly draw inspiration.

It's important that the viewer doesn't divide art by geography—they simply feel: is it a good piece or not. The main thing is the emotional and aesthetic impact.

— Was there a moment when you doubted your mission? Wanted to give it all up?

— Never in my mission. But thoughts of closing the gallery, of course, have occurred. This is a difficult and costly business. A gallery is not just walls and paintings. It's constant work: organizing processes, logistics, communicating with artists, interacting with the press, diplomatic missions, adhering to ethics. Tact and flexibility are important here. Sometimes difficulties arise, but I am always supported by the thought: what I do is truly needed by someone. That's what moves me forward.

— You mentioned that funds from the gallery are also used for publishing books. Could you tell us about the projects you have implemented?

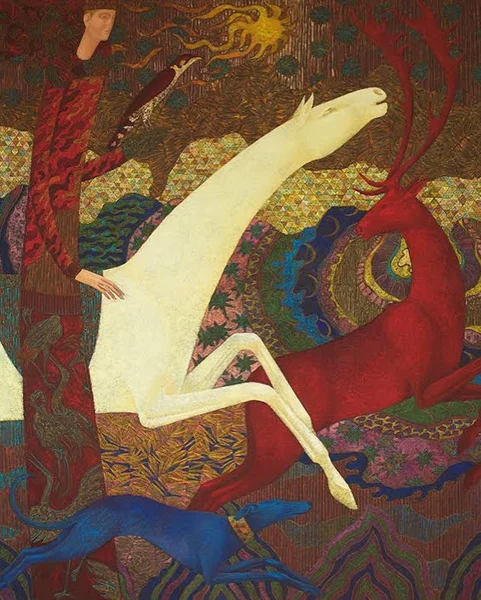

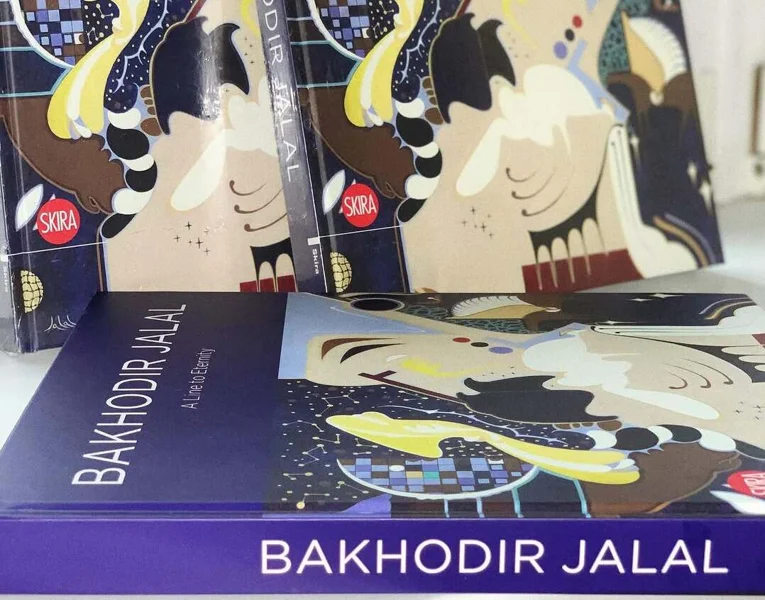

— The most significant is the monograph "Line of Eternity" by Bakhodir Jalal, published in English in 2018 by the Italian art publishing house Skira. This is our pride. For the first time, an artist from Central Asia became the subject of a book by a publishing house of such caliber. The edition contains over 200 color illustrations, analytical texts by art historians, and an in-depth review of his work.

Monograph by Bakhtiyor Jalil, Line of Eternity. Photo: Natalya Andakulova

A collector can be "created"

— You mentioned collectors. Do they often contact you?

— Yes, now they approach me regularly. But when I first opened the gallery—for the first seven years or so—I thought I had to find collectors myself. Everything changed when we started collaborating with Russian Social Club Dubai—a Russian-speaking cultural community. We began holding open lectures on contemporary art. I still conduct them every month.

And I realized one thing: a collector can be created. You can spark interest, engage them, and cultivate taste. A collection doesn't necessarily have to be a hundred pieces. Sometimes five are enough, but chosen with love and understanding. Hang them in your home — and it's already a small private gallery.

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— And who is the modern collector?

— The phenomenon of young collectors is particularly interesting now. After the COVID-19 pandemic, auction giants like Sotheby’s, Christie’s, and Artnet have noted a rejuvenation of collectors. More and more art buyers are under the age of 24.

According to Sotheby's, 40% of new clients at NFT auctions were under 40. At Christie's in 2021, 58% of buyers of digital art were millennials and Gen Z. This is being called the "second renaissance of art."

A collector today is not necessarily someone who "already has everything." It is anyone who wants to surround themselves with art. I always advise: start by asking yourself what you like. A region? A technique? History? Central Asia, Uzbekistan, graphics, miniature art—what is closer to you? And start small: acquire one good piece every two to three years.

Paintings are not bought to be stored in a safe. They live at home, on the wall, and create a mood. You wake up, walk into the room—and this work looks at you, inspires you. This is what real art is: personal, alive, meaningful.

And it's important to debunk the myth: art is not something inaccessible, closed off, like a Masonic lodge. You can buy a graphic work by a young artist for $150. It will be an original, an author's work, framed and 'fitted' into your home. The main thing is to want to surround yourself with beauty and meaning. And that's when true collecting begins.

— You say: "Create a collector." Have you actually managed to do this?

— Yes, and more than once! And each time feels like the first discovery, like the first kiss. When I give lectures, I always say: "Just give yourself a chance—open up to art, buy your first piece." And then the person gets hooked. They start with one painting, and then—the collection grows, taste develops, interest emerges. And that is incredibly joyful.

In Soviet times, art was everywhere — in the metro, in museums, in homes. It was part of everyday life. But there were almost no private collectors. There were a few — like, for example, Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov, whose collections were later taken away. Now is a different time — it's important not only to create art but also to share knowledge, to explain why it is important. To engage the viewer — including in the process of collecting.

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— You have a personal collection. Tell us about it.

— To be honest, I've never counted the number of artworks. It gradually grows. My collection includes works by Yuri Taldykin, Javlon Umarov, Bakhodir Jalol, Timur Akhmedov, Timur D'Vatz—mostly those artists I work with. Almost one or two works from each.

As for my husband, he is Bulgarian by nationality and collects exclusively Bulgarian art. In this sense, we have very specific interests, but they complement each other.

How art changes — and how it remains art

— What is your attitude towards contemporary art, which often provokes controversy and bewilderment?

— Contemporary art did not emerge yesterday. Its origins are in the 1970s, in postmodernism, as a response to the catastrophes of the 20th century. After two world wars, it became impossible to speak only of beauty—art became a way of comprehending pain and change.

With the advent of photography and video, the artist no longer needs to literally convey reality. The main thing is the idea. It could be glass, sound, an algorithm—any medium, as long as there is a thought behind it.

Already Marcel Duchamp with his "Ready-made" showed that a turning point in consciousness was occurring. And today, the artist fights for your attention in a world of information overload. He can shock, provoke, intrigue—but all of this is so that you will stop and think: "What is he talking about?"

— Do you accept digital art, artificial intelligence in art?

— Absolutely. For example, Dubai Airport features a work by digital artist Refik Anadol "Data Portal: Nature". He uses algorithms of sea movement, overlaying them with color data. It all flows, mesmerizes, literally 'sticks' in the mind. And now imagine — instead of that, hanging 200 paintings. Most likely, you would simply walk past. We have become insensitive to the conventional pictorial presentation.

— Have you ever had to work with provocative artworks in your gallery?

— I try to stay out of politics and religion. I believe that politics should be left to politicians, and religion to religious scholars. The art we represent is Eastern, subtle, full of meaning, and it requires a respectful approach.

Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— And what works would you never exhibit?

— Those that go beyond the bounds of morality. Of course, if a nude body is depicted with delicacy, professionalism, and taste—it can be considered. But art must never turn into vulgarity or provocation for the sake of provocation. We do not exhibit works on religious themes. As a rule, we select the artists' works ourselves: we make a selection, choose the best, what aligns with the gallery's aesthetic.

When investments are not about money

— You have spoken a lot about international experience. In which countries have you already held exhibitions and where do you plan to do so in the future?

— Currently, the main focus is on the Middle East. Saudi Arabia is very interesting, a promisingly developing art market. We previously had good contacts with Qatar. But overall, I am confident: good art is immediately visible, anywhere in the world. People feel beauty—whether in painting, music, or architecture. The main thing is that the work contains authenticity. Our artists are strong, with excellent training. And the East is always a crossroads of cultures. In the UAE, for example, locals make up only 18%, and the rest are expats from all over the world. There, the entire globe has literally "mixed," and in this diversity, all roads are open to genuine art.

— Are there any projects you have invested in particularly heavily?

— International fairs. This requires significant investments: from logistics to booth rental, artwork transportation, setup, and insurance. In my case, it didn't pay off financially, but it provided experience and an understanding of what to avoid in the future. The key is to be able to draw conclusions and not repeat mistakes.

— What was the most expensive job in your practice?

— Our prices are quite moderate. The average cost of a painting is about 3 thousand dollars, which is considered a reasonable price by international standards. Many people don't even contact us, thinking everything here is very expensive. But we don't work with "old masters" — by law, works older than 60 years cannot be exported. Therefore, we focus on contemporary art, mostly artists under 50.

The most curious case involved a young artist who valued one of his works at … one million dollars. All the others were priced at 300 dollars. When I asked, he replied that this painting was his talisman. I advised him to remove the price tag and not exhibit it at all — to avoid awkwardness. A million — that's money you could build a museum with! By the way, speaking of which, two new art spaces are opening in Almaty this year: Almaty Museum of Arts, created by Nurian Smagulov, and Tselinny Center of Contemporary Culture, founded by collector Kairat Boranbayev. That's where it's truly worth investing — where meaning will be born, where people come for inspiration.

— Do you collaborate with museums?

— We have made purchases, but so far – without a close partnership. Although one idea keeps coming back to me: several years ago we presented an exhibition in Istanbul called Genius Loci: Central Asia – "Genius of Place. Central Asia." It featured photographs by Max Penson – from the early 20th century, the 1920s–1930s, and video works by the Kazakh artist Almagul Menlibayeva – contemporary works, on the theme of the Aral Sea. It was a very powerful visual dialogue between eras and approaches.

Opening of Contemporary Istanbul. Photo: Natalya Andakulova

— Is there a dream you truly want to fulfill?

— Yes. I dream of presenting a contemporary art exhibition from Central Asia on a truly global level. So that it becomes a platform where our region's voice is heard loud and clear. We submitted an application to the Sharjah Art Museum several years ago. There's no response yet, but I believe it's still ahead of us.

What life could have been — and why everything turned out this way

— If you imagine that the gallery idea failed — who would you become?

— To be honest, I've never really thought about it seriously. But I suppose I would teach. Teaching is part of my nature. I still do it today—and I enjoy it.

— You can draw yourself. Have you ever wanted to have your own exhibition?

— When I first started learning painting, I thought: I'll retire—and then I'll take it up seriously. I really did have a dream to paint. I don't know when it will happen yet, but I know for sure—the time will come. I also want to do sports—I love golf. I've even been invited to tournaments, but I haven't played in a long time. I think I will definitely return to both sports and painting.

— If you compare yourself at the start of your journey and today—what has changed?

— Confidence has emerged. It comes with knowledge, with experience. I remember at the beginning, they looked at me like a child who came to play in a gallery. But now I feel an inner strength—and that changes a lot.

— If you could go back to 2016, or even a bit earlier, what advice would you give your former self?

— Don't doubt. Don't stop. Trust yourself and keep moving forward, even if not everything is clear right away. Be internally tuned to positivity, be able to self-motivate and inspire others. It works.

— What is happiness for you?

— Happiness is balance. Harmony between work and personal life. There should be room for sports, health, family, and professional fulfillment. When you develop your potential but don't forget about simple joys—that's when a true feeling of happiness emerges.