How Tea Culture Emerged in Uzbekistan

Uzbekistan is one of the most "tea-loving" countries in the world. According to data from Euromonitor International, 99.6% of the country's population prefers this drink over coffee. In Uzbekistan, tea is considered a traditional beverage, yet the tea-drinking culture formed here relatively recently.

According tothe opinion of Russian anthropologist and historian Sergey Abashin, tea had become an integral part of daily life in Turkestan by the beginning of the 19th century. Chinese brick tea was actively imported here through Kokand from Kashgar, and its consumption quickly spread throughout the region. The popularity of the drink was so great that when the Chinese closed the border in 1829, Kokandi merchants even attempted to force it open.

Immigrants from East Turkestan — the Kashgarians (later known as Uighurs) — played a special role in spreading tea culture, maintaining close ties with the nomadic Western Mongols. They were the first among the region's settled population to introduce a fashion for a variation of Kalmyk tea: it became customary to add salt, milk, kaymak (clotted cream) or melted butter (moy), and sometimes cracklings from mutton fat (zhiz).

The migration of Kashgarians and the general settlement of nomads in the 19th—early 20th centuries significantly influenced the tastes of local residents, especially in the Fergana Valley.

Gradually, Kalmyk tea with milk, fat, and salt began to give way to ordinary brewed tea. This happened after the adoption of the samovar from Russia, which made the tea brewing process simpler and faster.

Interestingly, by the beginning of the 20th century, teahouse keepers attempted to form a separate professional guild with their own charters and rituals. Abashin writes that at that time, to "professionalize" the craft, it was necessary to justify its ancient origin.

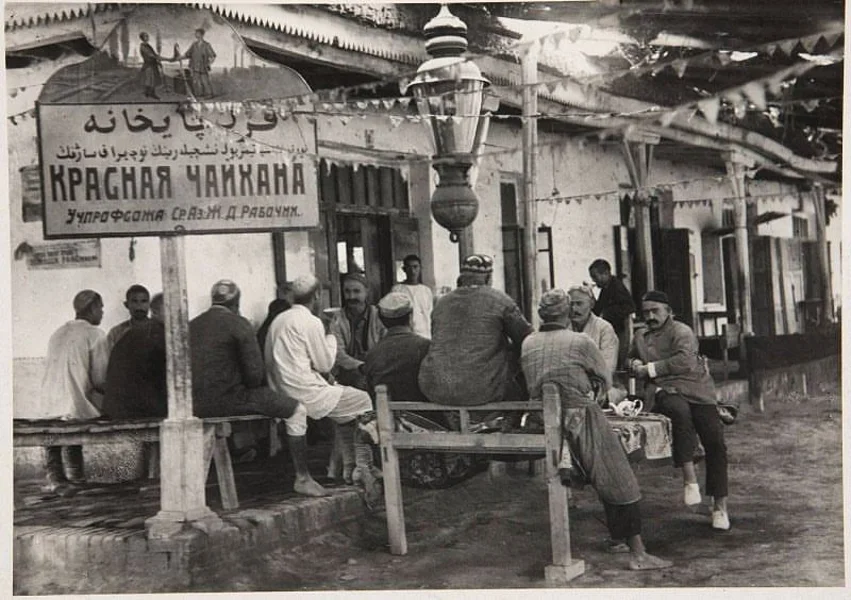

Teahouse in Samarkand. Photo: Peter Tierney

The Charter of "Tea House Keepers" established the following: "Once, the Prophet Muhammad set out with an army of companions to wage war against the 'infidels'; in the desert, the people were tormented by thirst, and Allah, in response to the prophet's prayer, provided water, but it was unfit for consumption; then another prophet, Dawud (the biblical David), appeared to Muhammad and showed him a stone that had the shape of a samovar; thanks to the stone-samovar, the warriors boiled the water and quenched their thirst."

Teahouse as a Cultural Phenomenon

Many Uzbek poets have celebrated the traditional teahouse — from Gafur Gulyam to Alexander Faynberg. Its influence on the culture of communication, the formation of public consciousness, and even the development of civil society in Central Asia is hard to overestimate. The teahouse became the first public and domestic institution in the Muslim East, and at the same time — the oldest form of networking. Here, people didn't just drink tea for a long time and with taste — they also discussed news, negotiated trade deals, and resolved family matters: from building a house to organizing weddings and funerals.

Here, storytellers gathered, Uzbek shashmaqoms and Tajik maqams resonated. Sometimes the teahouse turned into a ring — there were even special "boxing" teahouses where palvans competed in strength and agility. Sometimes it became an impromptu music salon, filled with the sounds of traditional instruments. For example, in the second half of the 19th century, the most honored guest in Khorezm teahouses was Palvan-Niyaz — a man who combined the talents of a composer, improviser, musician, and singer.

In different eras, the teahouse served as a kind of interest-based club.

Teahouses also hosted competitions of askiyaboz — masters of verbal dueling. The duel of wits was started by the one who poured the tea. Then he would pass the bowl to the next guest — and with it, the right to continue the verbal duel.

In the microcosm of the teahouse, the most famous artists of Uzbekistan found their best subjects. According to the words of Galina Abbasova, a methodologist at Moscow's Pushkin Museum, the image of the teahouse — is one of the most common motifs in the visual art of Central Asia. Alexander Volkov, one of the founders of the artistic school of Soviet Uzbekistan, dedicated many of his canvases, painted in warm tones, to this microcosm. This theme was also addressed by Alexander Nikolaev, Mikhail Kurzin, Bakhrom Khamdam.

Alexander Volkov, "Teahouse with a Portrait of Lenin".

From teahouse pilaf to teahouse ideology

If the Russian colonial administration in Turkestan tried not to interfere in the daily life of the local population, then the Bolsheviks, who came to power in the region after 1917, could not ignore such significant platforms for socializing the population as teahouses. In official documents of the 1920s, their role was assessed as follows:

"Teahouses (chaykhanas) play a very significant role in the life of the sedentary population of Central Asia. A teahouse exists in every village and serves as a unique club where public opinion is formed. It is clear, therefore, what great importance the organization of a wide network of red teahouses for cultural and educational purposes could have."

Following this directive, the new authorities began creating a "broad network of red teahouses." These were no longer just places of rest but centers of mass culture, propaganda, and education. Political slogans appeared here, the walls were adorned with portraits of Soviet leaders, and visitors could not only drink tea but also read fresh newspapers and pamphlets, and listen to lectures. Based on some teahouses, women's clubs were established, promoting ideas of equality. The red teahouses were intended to facilitate collectivization in the countryside, the imposition of the new ideology, and the formation of a "conscious" citizen.

The press of the early 1930s actively emphasized the significance of "red teahouses, red yurts, red chums": "...These new-type cultural and educational institutions have created a starting base for conquering new cultural heights. The contribution of red teahouses to the enlightenment of the masses, especially in rural backwaters, cannot be underestimated."

American researcher Claire Roizin writes that the reality "on the ground" differed from that in the newspapers. According to the testimony of one Komsomol activist, in the red teahouses of Uzbekistan, there was no interest whatsoever in the ideological literature sent there. Volumes of Marxist-Leninist classics were sometimes hung from the ceiling on ropes: one could reach out at any moment and tear out a page to wipe their hands or wrap food.

The Red Tea House on Urda, Tashkent. Photo: "Letters about Tashkent".

A visitor to the red teahouse was not supposed to come here simply to relax — a simple tea party without ideological subtext was condemned as "empty" and "devoid of ideas." Thus, the traditional teahouse in the early Soviet era was transformed into a tool for political education.

Over time, attitudes toward teahouses began to change for the worse. Already in the 1960s, Soviet press increasingly portrayed them as a symbol of outdated, "feudal" traditions. Newspapers and the satirical magazine "Mushkum" cultivated a critical image of the teahouse—a "place where chatterboxes and idlers gather." Cartoons of that time mocked the habit of men spending time in teahouses, especially during the cotton harvest. "Mushkum" published caricatures of puffy tea enthusiasts lounging on couches while women did the hard work in the fields.

And yet, the teahouse remained what it was originally: a living social organism, a repository of folk traditions. Just like a hundred years ago, leisurely conversations about everyday matters are held in the teahouse, and tea is poured for one another. The bowl is supposed to be filled halfway — this is a sign of respect, allowing one to drink the cooled tea faster. Filling the bowl to the brim — is bad manners: it means the person came here simply to drink tea — and thus, is not fit to be an interesting conversationalist.