He sent the caravan to Tashkent and dispatched two officers with it for geographical observations.

This is from Pushkin's note "On Tatishchev," written presumably in 1836. It was not published during the poet's lifetime and was found among his papers. Nevertheless, it is with this note that the name Tashkent appears in Russian literature. Precisely with Pushkin.

And I shall be glorious, as long as in the sublunary world…

Of course, Pushkin could hardly have imagined then that in just a few decades, Tashkent would enter the geographical realm of Russian literature, appearing on the pages of Fyodor Dostoevsky, Leo Tolstoy, Leskov... And certainly not that in this remote Asian city, which could only be reached by caravan, there would appear a Pushkin Street, a Pushkin Park, a Pushkinskaya metro station... And, of course, a monument to the poet. The street and the park, however, were eventually renamed, the monument was moved (and they even gave the name "Pushkin Square" to the place where it now stands). The metro, fortunately, remains, without any renaming or alterations; and for that – thank goodness.

Most importantly, the "merry name of Pushkin" has been preserved in Tashkent. And it even slightly rhymes with it. "Tashkent" – "Pushkin." Can you name another capital that would be so harmonious with the poet's name...

But, even more importantly, the language remained. The language of Pushkin. The language of Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky – who never visited Tashkent. The language of Anna Akhmatova, Alexei Tolstoy, Konstantin Simonov: not just visitors – but those who lived in Tashkent. The language of many writers born and living in Tashkent, in Uzbekistan. And not only writers. Scientists, artists, engineers, entrepreneurs, journalists, workers, builders, schoolchildren, pensioners... Uzbeks.

Pushkin Monument in Tashkent. Photo: Katerina Kuznetsova

A language of high culture – and simultaneously, alas, of the coarsest and most offensive profanity. A language of refined poetry – and of primitive chanson. The language of the street, universities, back alleys, libraries, the latest news, clinics, and gyms… A language that still remains the second most widespread after Uzbek. Engaging with it in complex relationships of exchanging words, expressions, intonations.

What is the status of the Russian language in Tashkent today — and more broadly — in Uzbekistan?

The question is both simple and complex.

Complex, because there is no clear statistics yet. Only a population census can provide a picture of who speaks which language and to what extent. The last one in Uzbekistan was conducted back in Soviet times, in 1989. According to UN norms, a population census should be conducted every ten years. This provision is reflected in the Law on Population Census, adopted five years ago, in March 2020. But there has been no census yet; it is supposedly planned for next year. Good, then we'll look at the numbers, and it will be possible to say something definite about the number of Russian speakers in Uzbekistan and their distribution.

On the other hand, the question about the Russian language is quite simple.

Just travel through the largest cities of Uzbekistan, walk along the central streets, listen to the linguistic hum. Take a closer look at the signs. Ask the first person you meet a question in Russian. And understand that Russian is present. More so in some places, like, say, in Tashkent, Samarkand, or Fergana—less so in others, and sometimes—almost at the level of infinitesimal quantities.

And not only geographically. It is more common among the older generation than among the youth. Among the intelligentsia and entrepreneurs—it occurs more frequently than among peasants. But it was the same before, even before 1991. Only the proportions have changed.

Yes, the Russian language is declining. But it's declining in all former Soviet republics. In some places, it's happening faster (as, for example, in Lithuania), in others—slower (as in Kazakhstan). And the reasons are the same everywhere. The change in the former status of the language after gaining political independence. A significant outflow and relatively low demographic growth of the Russian (and generally, Russian-speaking) population.

However, the models of relations between independent states and the language of the former metropole vary worldwide. There is India, where the English language retains official status. There is Algeria, where Arabic is primary and dominant, but about one-third of the population speaks and reads French fluently. And there are the Philippines, where the Spanish language, which was still in use as recently as the 1950s, has almost disappeared, supplanted by English as the second official language.

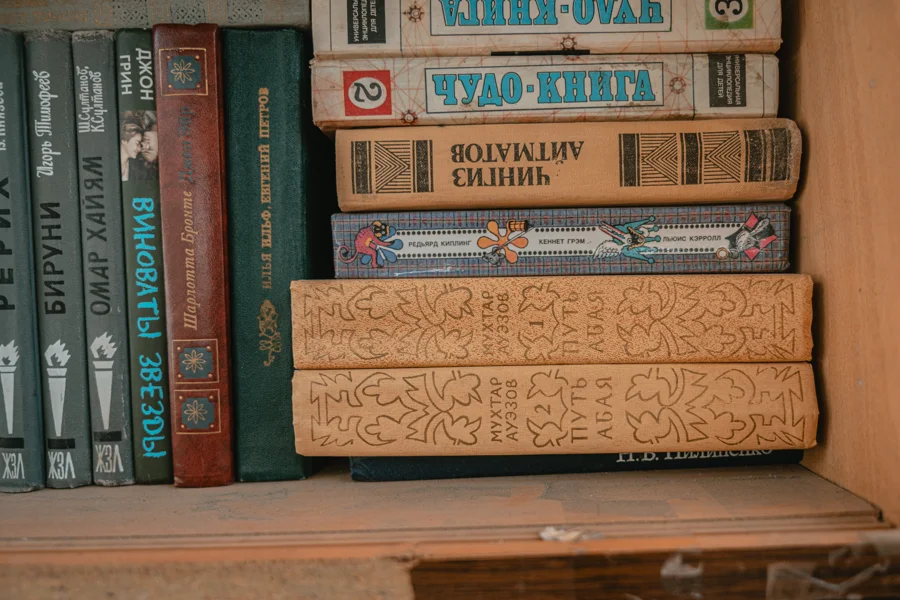

The second-hand book market in Tashkent. Photo: Katerina Kuznetsova

What awaits the Russian language in Uzbekistan?

It's difficult to say, too many different factors are at play here. Political, economic, demographic, cultural… For now, the situation with the Russian language is closer to that of Algeria than the Philippines. People continue to communicate in Russian—both within the Russian-speaking community of Uzbekistan and between different nationalities, and—which is also important—between the various peoples of Central Asia… One example. At the end of October last year, while in Dushanbe, I stopped into a cafe for dinner. There was a lively conversation at the next table: young Uzbek businessmen who had come on business were talking with their Dushanbe partners.

In what language was the conversation between them conducted? In Russian. In a language understandable to both. In one of the languages of international communication. In the language of Pushkin.

So, dear, beloved Alexander Sergeyevich, it is no coincidence, no, not at all, that you mentioned Tashkent – you must have sensed something. You have become almost a local resident in Tashkent. Neither your light tan nor your dark curly hair would surprise anyone here. Your poems are studied in schools here, and plays based on your works are staged. And not just in Tashkent, but throughout Uzbekistan.

And probably, as long as you are here, as long as your name and your poetry hold significance in Central Asia, the Russian language will remain here as well. That very language about which you once wrote so wonderfully: "...the Russian language, so flexible and powerful in its constructions and means, so receptive and sociable in its relations to foreign languages...".