Step by step: how "Shagayu.uz" became an urban movement

— Tell us how the "Shagayu.uz" initiative came about?

"Today, everyone counts steps—10,000 a day. But in 2017, this was a novelty. Apps were just starting to appear, and enthusiasts were sharing screenshots. And I thought: what if I walked consciously? Looked around, understood where I live?"

Around the same time, I and the group "Young Photography of Uzbekistan" found ourselves at an exhibition in the House of Photography. After the exhibition, we simply went for a walk around Tashkent with our cameras: photographing faces, light, the city.

Then the group disbanded, but I was left with an idea: to walk with attention. And on May 6, 2017, I wrote the first announcement in the public group "Excursionmania." The next day, we met near Mirzo Ulugbek Park — and set off. We simply walked, without a guide, without a goal, except for one — to see our city differently. That's how the group "Walking in Tashkent" was born.

Logo of the "Shagayu.uz" project

— How did the participants react?

— The format caught on. To walk, to look, to talk, and sometimes — just to be silent. People were surprised: "Are there such places in Tashkent?" — Of course there are! And many. Fifty-six people came to one of the walks — and I realized that people needed this. We were discovering the city — step by step. And it was truly meaningful.

— The project started as a city initiative. How did it grow into something bigger?

— In 2017–2018, we started traveling beyond Tashkent — first to the suburbs, then to the mountains. The first routes were simple: Sukok, the Sun Institute. Back then, Sukok wasn't considered a popular destination — no commerce, no tour companies or guides. We would meet in Kuilyuk, get to Parkent, and then take multiple rides to the reserve. Everything was built on enthusiasm. Of course, organized tours replicating our routes appeared later, but for us, it was romance — pure discovery.

Gradually, the geography expanded: we began venturing into neighboring republics. One of the highlights was December 2018, when we first traveled abroad. First, to Khujand in Tajikistan, then to Shymkent in Kazakhstan. All expenses were covered by the participants themselves. We returned tired but full of impressions.

— During the COVID-19 pandemic, many things changed, including in the tourism sector. Did this affect your projects?

— Of course, COVID made its own adjustments: we had to gather less often, go out more alone or in small groups. But the habit of exploration remained. I tried to choose places where the foot of a mass tourist had not set foot — that is still my principle.

— What particularly draws you to such trips?

— Abandoned cities. Yangiabad in Uzbekistan, an old mining town in Tajikistan... We were the first to go there. Then came commercial tours, then interest from local authorities. For example, Yangiabad is now developing its infrastructure, and tourist projects have appeared. And I see a result in this: such places are coming back to life. So, it was worth the effort.

As you walk — the city comes to life

— Do you still organize city walks?

— Now — much less often. If I do go out, it's thematic routes: walks focusing on mosaics, Chilanzar, sometimes quizzes or quests. Simply guiding people no longer interests me — my perception of time has changed, and I've gained a different understanding of the value of knowledge.

— And all of this doesn't generate revenue?

— It took me seven years to formulate an honest answer to the question: 'Why don't you monetize the project?' I always answered: 'Because I'm not a professional guide, I don't have a license.' But last year, I finally completed the courses and got a diploma. To be honest, much of what they taught, I did intuitively — I scouted routes myself, calculated logistics, estimated time, knew where to turn, where to stop. Officially, I don't work as a guide now, but if I'm called again — I'll put on my sneakers again, take my camera, and go. And the city will come with me.

— And outside of Uzbekistan — what inspires you in your travels?

— I travel alone and not for very long. But I've already been to Baikal, India, London, Bhutan. Many people are afraid to travel solo, but fear is mostly in your head.

Baikal amazed me with its silence, Bhutan with inner peace and absence of tourist bustle. I got to Europe for work — a conference in London, and then I dropped by Scotland. I don't chase brands — I invest in experiences.

— What about non-touristic routes within the country?

— I adore rural routes. For example, the settlement of Varganza in Kashkadarya — there are entire pomegranate orchards there. Although they were severely damaged in the winter of 2022–2023. Or the Arab diaspora — settlers who weave unique flat-woven kilim carpets, women in traditional clothing. It's like a living museum.

From Varganza, Uzbek street artist Vargunza, read our interview with him:

In London, I was struck by the approach to souvenirs—each museum has its own set. This is smart marketing: a tourist leaves not just with a magnet, but with an impression they want to repeat. Here, everything is the same. A lot is lost, even though the potential is huge. We underestimate our own strengths.

From walks — to the archaeology of the urban mosaic

— How did your interest in Tashkent mosaics begin?

— It didn't happen suddenly. It's just that one day I noticed I began to see things that had previously escaped my notice. We were walking around the city, and I was paying more and more attention to the mosaics decorating the facades of buildings. By then, I was already a member of the Facebook community "Young Photography of Uzbekistan" and was publishing my photos — amateur ones, taken with a phone, but sincere.

And then one day I saw Oleg Burnashev's post — he announced the creation of a new group called "Mosaics of Uzbekistan" and suggested sharing photos of mosaics encountered during city walks. I responded immediately: I already had photos, and I started posting them to the group. Soon, Oleg wrote to me personally. He suggested contacting Valentina Zharskaya — the widow of the artist Nikolai Zharsky — and their daughter Tatyana, in case they had preserved archives. Of course, I wrote. I had many questions.

Valentina Alekseevna turned out to be a very open person. We got to talking, and she advised meeting with Yuri Georgievich Miroshnichenko — the chief architect of the «Tashgiprogors» institute and a close friend of the Zharsky family. He recounted that after the 1966 earthquake, the Zharsky brothers — Pyotr, Nikolai, and later Alexander — arrived in Tashkent. Initially, they worked at "Tashgiprogors," then moved to the house-building plant DSK-1. There, among the construction debris — broken tiles, ceramic fragments — the idea was born that would change the city's visual appearance. Some saw it as junk, but they saw mosaic material.

The Zharsky Brothers also created a series of mosaics dedicated to Space, read our article:

Pyotr Zharsky created the sketch for the first major work and showed it to Miroshnichenko. The composition was bold—people in national dress, mythological creatures, a red ribbon, ornaments… There was a temptation to refuse. But Miroshnichenko decided to talk to the artist—and before him opened up not only a professional but also an incredibly interesting person: Pyotr studied in Leningrad, lived in France, graduated from the Mukhina School. After this dialogue, the sketch was approved. And soon, on Mukimi Street, the first mosaic appeared—daring, bright, alive.

Mosaic on Mukimi Street in Tashkent. Photo: Fotima Abdurakhmanova

No scandal occurred. Tashkent accepted it. And an entire era began: from Kartartal to the twentieth quarter of Chilanzar, houses with mosaics appeared one after another. They became part of the urban environment—vibrant, free, colorful.

At first, it was only residential buildings whose facades bloomed under the hands of artists. But I became curious: who created the mosaics on public buildings? Who are the authors? Thus began my own search.

From Photo to Book

— At what point did your project go beyond walks and personal interest?

— Everything changed when I became acquainted with the works of Philipp Meuser, a German urbanist deeply interested in the architectural heritage of the Soviet era. He personally knew Nikolai Zharsky, studied housing construction across the entire post-Soviet space, and assembled extensive archives: photos, texts, books. In his approach, architecture is not just concrete and glass, but a mirror of cultural memory.

He was the one who proposed creating a guide to Tashkent's mosaics—oriented towards foreign tourists. But he didn't need just a photographer; he needed someone who could bring the objects to life with historical and cultural context. Not just "address, date, author," but a story: what is depicted, what ritual, what symbols. For example, the mosaic on the facade of the Uzexpocentre—an Uzbek wedding. For a local, it's clear, but a tourist needs an explanation. Then the mosaic becomes a bridge between cultures. This resonated with me—and I joined the work.

And also, Philip Moiser wrote a column for us about the construction of Soviet cities. Read it:

— Who helped identify the authors of the mosaics?

— First and foremost — Yuriy Myroshnychenko and Valentyna Zharska. Thanks to their memory, I managed to understand which works belong to Petro or Mykola Zharsky, and which — to other masters whose names have remained only in oral history.

— Did you manage to implement the guide?

— In 2019, the project was put on hold due to a lack of resources. But in 2023, Philipp got back in touch: he had finished a book about the Zharsky brothers—with my photos, taken back then. He came to Tashkent again, continued his research, filming, meetings. He said the guidebook would indeed be published—and would include not only mosaics, but also frescoes, sculptures, bas-reliefs, everything that forms the visual soul of the city.

Photographs of Tashkent mosaics for Philip Moizer

Then another interesting meeting occurred. I was contacted by journalist Valeria Nayanova, the author of the YouTube channel "Po Matryoshkam" (By the Matryoshkas). She decided to make a film about the mosaics of Tashkent. I introduced her to Yuri Miroshnichenko, Valentina Zharskaya, and Vladimir Burmakin—all of them appeared on camera. The film received a strong response—both in Uzbekistan and beyond its borders.

This became a turning point for the project — this film was seen by Utkir Shermanov from the Department of Digital Development. And the idea was born there — to create a website about Tashkent's mosaics. Alexey Khen, the art director of Age Tashkent, and I discussed the structure of the portal. I collected everything: photos, names, addresses, sources. And then a message came from Philip: he would come in April for a book presentation. That's when I suggested: let's launch the website just before — we'll have a double cultural launch. This is not commerce. This is memory, meaning, the city.

A website dedicated to Tashkent mosaics. Screenshot

When mosaics come to life

— What was the reaction to the site launch?

— Very inspiring. We didn't just gather mosaics in one place—some of them literally came to life. Thanks to animation, you can now download a special app, point your phone's camera—and the mosaic begins to move, breathe, tell a story. It's real magic.

— How many objects were documented?

— Currently, the website features 502 mosaics. Unfortunately, 17 of them have been lost. However, what remains already forms a significant layer of visual memory. The main thing is that these objects are now systematized, accessible, and protected. After all, a documented object is not so easy to destroy. Sponsors have emerged, giving us a second wind. One of the most important steps was the removal of advertising banners from facades adorned with mosaics. It was not easy: commercial interests, contracts, landlords... But there is a result — the banners have been taken down, and the city has "breathed."

— Has official protection of the mosaics been established?

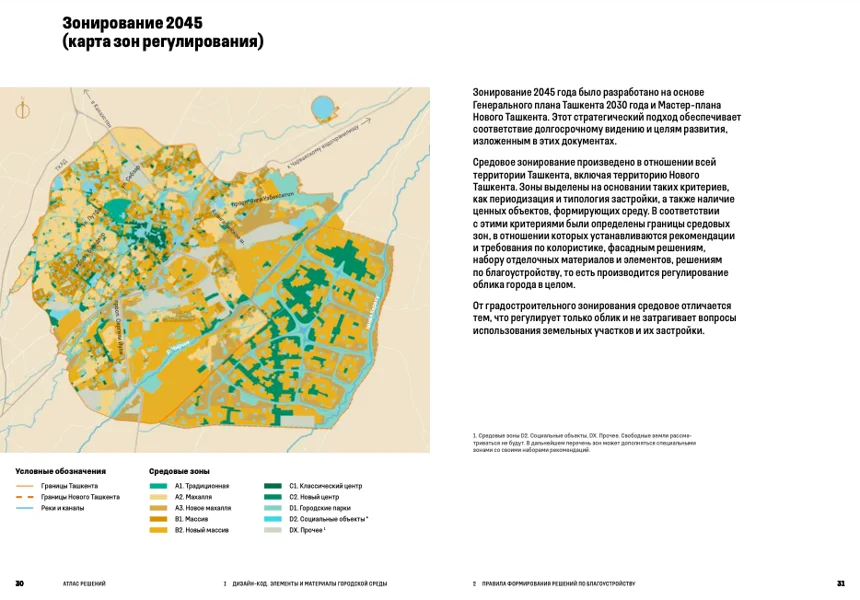

— Yes. In the fall of 2024, the New Tashkent Construction Directorate released a document — the "Urban Environment Design Code". It clearly states: if a facade has a mosaic, advertising is prohibited. Violations entail administrative liability. This was an important step: we were heard.

"Urban Environment Design Code" of Tashkent. Screenshot

We have also teamed up with Philip Moizer again and decided to release a guidebook alongside his book. The work is almost complete now. This will not be just a map, but a cultural journey through the mosaics of Tashkent—with history, with a voice, with a living perspective on the city.

New Discoveries, New Names

— Do you continue to search for and find mosaics?

— Yes, and sometimes completely unexpectedly. Once, Daria Petrova wrote to me — a Russian woman, daughter of a monumental artist who once worked with Vladimir Burmakin. Her father left Uzbekistan in 1995 and passed away in the early 2000s. Daria sent photos of him assembling a mosaic in the courtyard of a kindergarten in Urda. A warm, kind work, created for children. I went there — and found this piece. A new mosaic, a new name, a new story.

The same was true for the "Wedding" panel on the facade of the Uzexpocentre. For a long time, we could not determine who the author was. And then suddenly, a young man contacted me – the grandson of the author of this "canvas," Dilmurod Yusupov. He provided documents, photos, we got in touch, and in the end, we managed to restore the artist's biography. It was like a revelation.

The "Wedding" panel on the facade of the Uzexpocentre. Video: "Shagayu.uz"

— So the search for authors continues?

— This is one of the main areas. We often have to revisit already established versions. Here's an example — the mosaic at the entrance to the Textile Institute. They wanted to paint over it, but one of the vice-rectors defended the panel. A wave of support rose on social media, and soon a representative of the Heritage Protection Agency stated that the author was Irena Lipiene. But I had doubts: Lipiene is known for stained glass, glasswork, but no mosaics were attributed to her. In the end, it turned out that the real authors were Alexey Shteyman and Grigory Derviz. The mosaic was created in 1982.

— What about the lost mosaics?

— Currently, 17 lost objects are listed on the site. But recently, there were 19. Two works have been successfully returned: sponsors helped restore the mosaics that were painted over as part of the «Obod Mahalla» program. They paid for the work of the climbers and the materials — and within two days, the images were shining again. Their status on the portal has changed: they are back with us.

— Which mosaics are still waiting for their chance to return to the city?

— There are works that can be saved. But it's important to understand: this is not just an act of goodwill. Even cleaning a wall requires official permission. Everything must be coordinated with the Agency for Cultural Heritage Protection and the Cultural Development Fund. This is not a formality. The Fund accompanies the project at every stage, provides consultations, and assists. Without it, no responsible decision is possible. And that's right. Because a mosaic is not just a pattern; it is the cultural code of the city. And it must be handled with care.

Why mosaics disappear

— Why did the mosaics start disappearing? After all, this is cultural heritage...

— I don't think anyone deliberately destroyed them. Everything happened spontaneously—in an atmosphere of indifference, bureaucracy, and lack of taste. After gaining Independence, a wave of large-scale reconstructions began. Old buildings were demolished—to make way for new offices, residential buildings. Often, no one even noticed that there were mosaics on the facades. For example, the 'Trudovye Rezervy' sports complex. It was demolished, a new one was built—and along with the building, the mosaic disappeared. No photos or mentions have survived. The same goes for the mosaic in the House of Knowledge: in the early 2000s, a reconstruction was underway, and everything vanished without a trace. Although later, architect Yuriy Miroshnichenko said the panel remained—it was just covered by drywall. But another researcher, Boris Chukhovich, wrote that it was lost. And all we have now is hope.

Panel in the "Trudovye Rezervy" sports complex. Mosaic "Running Olympian". Source: Letters about Tashkent

— Did you try to verify this?

— Yes. Last year, during the renovation of the Russian Drama Theater, I accidentally saw a piece of the old wall through the dismantled cladding—a fragment that might be part of that very mosaic. I managed to photograph it. Only one thing remains—to carefully open it up and check.

— What about particularly bright but damaged mosaics?

— It's very painful to look at the mosaic panel near Amir Temur Square. A magnificent composition made of smalt — symbols of the Amu Darya and Syr Darya rivers, vivid, bright colors. But the female figures had exposed parts of their bodies — and they were simply painted over with gray paint. Technically, this can be restored, but no one dares to do it. It's too 'inconvenient' a job for an area with strict architectural standards.

— Is there growing interest in mosaics among the new generation?

— Yes, and that's pleasing. Young artists, designers, and architects are increasingly paying attention to mosaics. In cafes, hotels—decorative panels are appearing. It's becoming part of the city's visual language.

— What modern projects inspire you?

- Center of Islamic Civilization. There, mosaic became the key element of the design. The sketches were created by Alisher Alikulov, they were assembled in China using templates and returned to Tashkent. The themes are history, spirituality, enlightenment. And most importantly, the choice was made in favor of mosaic, despite its complexity and high cost.

— In Soviet times, was everything done by hand?

— Yes. Smalt — dense colored glass — was brought from Leningrad and the Baltics. It was crushed, chipped, sorted by color, and laid by hand. It was a labor-intensive process. Now smalt is hardly used. Even Chinese masters used a different glass — smooth, uniform. In appearance — beautiful, but in essence — it's something completely different.

— What other types of mosaics can be found in Tashkent?

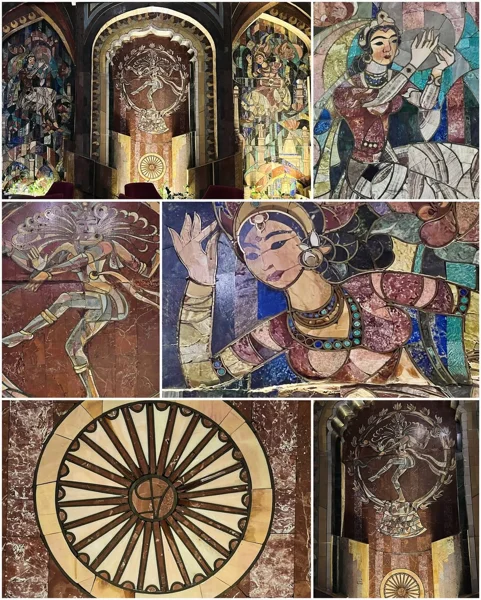

— The rarest and most valuable is Florentine mosaic. Abdumalik Bukharbaev used it in his works — in the television center, the former "Tata" hotel, and at the "Novza" and "Uzbekistanskaya" metro stations. It's a jewelry technique — jasper, granite, marble, stones without seams, fitted edge to edge. A truly unique work of art.

Mosaic panel in the lobby of Le Grande Plaza Hotel (formerly "Tata"). Photo: Fotima Abdurakhmanova

— What about the mosaics with Soviet symbolism? Have they been preserved?

— There are some, but not many. And it's not propaganda, but part of the visual memory. For example, the mosaic on Karakamysh: a dove of peace, a hammer and sickle. No one touches it. Or the mosaic on the panel building — a worker with a bare torso, next to it — pioneers by a campfire. The symbolism is incorporated softly: flowers, butterflies, a harp. It's history now. The Zharskys, in their later works on the Vodnik massif, depicted scenes from life: weddings, couples, children. Everything is alive, human.

— But aren't there exceptions?

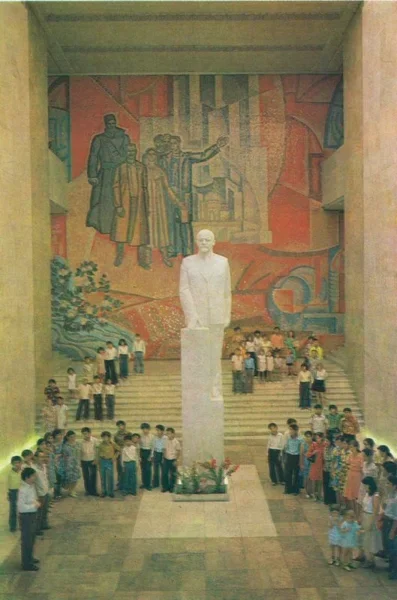

— Of course. The most famous one is the mosaic with Lenin in the former museum, now the Historical Museum. It was painted over, with a landscape on top. But, according to rumors, it has been preserved under the layers. This is perhaps the only ideological mosaic in the city. We don't want to erase the past — we want to make sense of it.

The central hall of the V.I. Lenin Museum in Tashkent. Source: Letters about Tashkent

— Have there been cases where mosaics were successfully saved?

"Yes, this is a mosaic by monumental artist Arnold Gan on the building of the newspaper production facility. When the decision was made to reconstruct the building, we proposed preserving the panel. Various options were discussed—for example, moving it to a park. But the mosaic is enormous. It was dismantled overnight, and by morning it was already gone. The Cultural Foundation assured that it would be installed in the courtyard behind the former 'Tata' Hotel, where they are creating a cultural center. It is currently in storage. But now, according to reports from some media, the mosaic will be installed in the French Cultural Center. This is a work that needs space. Perhaps it's worth creating an open-air museum—like the 'Muzeon' art park in Moscow."

— Where can such a space be organized?

— Somewhere between the old and new Tashkent, closer to "Yangi O'zbekiston" park. There's still space there for now. Let it not be a museum, but a gallery. Like in "Kok-Tobe" park in Almaty: the mosaic "Girl with a Souvenir" ("Sulushash") by artist Moldakhmet Kenbayev stands in a frame on the mountainside—it doesn't get in the way, but it speaks.

Lost but not forgotten

— Are there any mosaics that you are particularly fighting for?

— Yes. The most important one for me right now is "Farhad and Shirin." These are two panels on adjacent facades: one shows Shirin, the other Farhad. They are strong in composition, rich in symbolism. But the mosaic depicting Farhad has been severely damaged: sun, wind, precipitation—all have eroded the surface. Moreover, it was assembled by hand at a house-building plant and mounted directly on the facade. That technique is no longer used today, and that type of smalt is no longer produced—it was bright, textured, vibrant. Restoring it to its original state is impossible. But it is possible—to document it, to preserve the narrative.

I consulted with Marina Rostislavovna Borodina, an academician of the Academy of Arts. She proposed a solution — 3D printing of the image on the wall. Yes, it's not a mosaic in the classical sense, but a mural. But if this is the only way to return "Farhad and Shirin" to the urban space — then it's worth trying.

— Are there any more such mosaics that can be saved?

— Yes. For example, the mosaic in the House of Knowledge, which I already mentioned. According to architect Yuri Miroshnichenko, it is not destroyed, but simply covered with drywall. All that remains is to decide to verify it. Or the two mosaics by Abdumalik Bukharbaev in the Palace of Friendship of Peoples — they are intact but covered with banners. They don't need restoration — just to be uncovered. And also — the mosaics on the facades of the "Uzbekenergo" complex. It will most likely be demolished. And if we don't save these works in advance — they simply won't exist.

Mosaic in the former House of Knowledge. Source: Letters about Tashkent

— Were there any cases of irreversible losses?

— Unfortunately, yes. My favorite mosaic is "Swan Loyalty" by Vladimir Burmakin — two white swans, a symbol of purity and tenderness. I included it in a book in 2019. And then the pandemic came, the building was sold, and the new owner erased the mosaic. Not a single fragment or archival photo remains. Only pain. Around the same time, the driving school with its decorative panel disappeared, and the House of Culture was demolished. Everything vanished in silence — without documentation, without records. And that's the most terrible part — when there isn't even a trace left.

— Were the mosaics saved at the last moment?

— Yes, such cases are inspiring. In one residential complex, the new owners wanted to dismantle the mosaic and take it for themselves, inspired by bloggers. But without proper approvals. I explained that permissions from the Culture Fund and the Heritage Protection Agency were needed. Fortunately, we managed to stop it — the mosaic is still in place, just hidden behind a screen. This is the 'Kitob olami' building, and it contains a true masterpiece. Just remove the monitor — and the building becomes a landmark. It's preservation, a cultural contribution, and successful PR.

"This is not background noise — this is the voice of the city"

— Have you already presented the project? What were the responses?

— The first one was held at the Goethe-Institut in Tashkent. The audience was narrow. I immediately said: 'It's not enough. We need a press tour, we need bloggers, activists.' They were invited. They were paid. But there was no engagement. A couple of photos — and empty gazes. They didn't feel the topic, they weren't in it. But they should have invited students — architects, designers, artists. This is their professional field, their future. They are the ones who should see, understand, and carry it forward. We need an audience that cares. Not those who use mosaics as a beautiful backdrop for photoshoots, but those who genuinely want to know and preserve. Because mosaics are not just decor. They are the voice of the city. And it needs to be heard.

Fotima Abdurakhmanova and the mosaic panel with Taras Shevchenko

— Do you appeal to contemporary artists?

— Yes, often. I ask directly: 'Why don't you create your own? Why are there only old motifs in the renders? Where are the visual images of today?' A young guy recently wrote to me on Instagram: 'I've started making mosaics, I want to depict Samarkand, Khiva. Do you think anyone needs this?' I replied: 'Do it. Try. The main thing is to show yourself. If you don't tell about yourself — no one will know.'

— What mosaics would you like to see in the future?

— Just no clichés: no 'hands reaching for the globe,' no abstract 'tree of life.' Let the themes be those that truly concern us today: the city, loneliness, technology, migration, ecology, women and the metropolis... The main thing is to do it with taste, with thought, with respect for the material. Art should be alive.

— And if you could order a mosaic from the Zharsky brothers?

— I would ask for a narrative one—— with images of people, with a story. Those are the ones that truly resonate with me. That's why I love Tajik mosaics so much — they almost always have characters, scenes, emotions. They are naive, bright, but with soul. Soulfulness — that's what we often lack. We have many ornaments — beautiful, but often empty. And when there is a person in a mosaic, it comes to life.

— Which mosaic started your personal history?

— From the "Aquarius" mosaic. It's on the facade of the former dormitory, which now houses the Association of Accountants and Auditors. I went there for courses — I am an accountant by education. After class, I went out, approached the intersection, looked up — and saw it. I froze. Took out my phone. Took a picture. It all started from that shot: my mosaics, my "steps," my story.

"A photograph can preserve what no longer exists"

— Everything starts with a photograph for you. But was there that one specific photograph that changed something for you?

— I'm not sure there was just one, but there were cases when photos became a starting point. Once, my group and I were walking around the Lisunov district and peeked into an abandoned building. Inside were teenagers. They unexpectedly offered to show us an "interesting place" — and led us to an unfinished swimming pool. Construction had started back in the 1980s but was frozen. We crawled through the fence, photographed everything, posted it on social media. After a while, the pool began to be restored. Today it's operational. I'd like to believe our photos gave it a push.

When it became known about the demolition of the Ukchi Olmazor mahallas, I went there almost every day. First with a group, then alone. I photographed the dilapidated walls, empty windows, remnants of coziness. I knew: this needed to be documented. Now I have a whole archive of these streets. They are gone. But the memory remains.

There was another incident: a friend called me - "They're demolishing the House of Cinema!". I went there, met director Rashid Malikov. He took me to the management - and they allowed me to document everything. I photographed the halls, corridors, the famous fresco by Bakhodyr Jalal. It's gone now. But it remains - in the photograph. In the archive. In memory.

House of Cinema building. Source: Letters about Tashkent

Read our interview with Bahodir Jalol:

— What is Tashkent to you?

— It's not just my hometown. It's the rhythm I live in. That's why the idea emerged not just to stroll, but to live the city. Consciously. To share it. From 2017 to 2025, we've taken hundreds of steps — with the "I Walk Tashkent" project. During this time, the city has changed beyond recognition. Sometimes I return to a familiar place — and can't believe my eyes: everything was different just yesterday.

"A city is not a point on a map, but a conversation partner"

— How do you feel about the modern reconstruction of Tashkent?

— I have mixed feelings. On one hand, the renovations make the city well-kept, comfortable, with the emergence of gastronomic streets and tourist attractions. On the other hand, there is a risk of losing authenticity. Local activists often protest: why change the old streets, touch what is already alive? And I understand them. But if the spirit of the place is preserved—then it's all worthwhile. Cafes and guesthouses are opening in former mahallas. The districts are becoming stages where tradition and modernity meet. And tourists take away not only photos but a genuine impression. Development is a journey. And we are on it.

— What do you think of the new city installations?

— We have a problem with small architectural forms. There are almost no artistic sculptures in the city. And the ones that do appear are tasteless, made from fragile materials. Sometimes it feels like a good rain will wash them all away. In other countries, you see bronze, marble, scenes from life. In Baku, for example, along the embankment, there's a whole gallery of images: a man with a newspaper, a shoe shiner... Here, we just have mass-produced, meaningless figurines.

— And do you continue to photograph yourself?

— Of course. Nowadays, it's mostly on the phone — the technology allows it. But on trips, I take a camera: a shot taken through a lens is a different quality of perception. Although the main thing is not the equipment, but the eye. The ability to feel the moment, to build a story within the frame.

— Are you still "walking"?

— It's already part of my life. I have my pedometer on — I try to walk at least 10,000 steps a day. A walk isn't just physical activity; it's a way to be in the city, to see it. You're walking along — and you notice: an old sewer manhole with a pattern, a Soviet-era pole propped up by a railway sleeper with a date carved into it. Or — two buildings side by side: one is high-tech, the other has wooden shutters. It's a chronicle. Layers of time.

Fotima Abdurakhmanova at Pakhtakor metro station

And I also do plogging – I always go out with gloves and a bag. I collect trash along the way: bottles, wrappers – especially near schools. It's cleaner now – so it works. This is also part of the culture – respect for yourself, for people, and for the city.

— And you've started to see mosaics differently, haven't you?

— Of course. Mosaic is not just decoration. It is text, language, gesture. Here, for example, is Pyotr Zharsky's first mosaic: people, ornaments, animals, everything is arranged in rhythm. One of the figures holds a ribbon, with a crossed finger — that is a symbol, a protective charm. They built into houses not only beauty but also protection. It is profound. You just have to look.

— What would you say to those who don't yet know their city?

— Learn about it, but most importantly — fall in love with your city. Without love, it's impossible to understand. We often complain, criticize, but forget: the city is not someone else. It is us. It's our actions, our traces. That's why I say: walk. Look. Notice. Breathe in the city. And it will definitely speak to you.