About his mother's iron fist

— You were born in Namangan, but your family's story began in another city.

— That's right. My mother and grandmother lived near Stalingrad, but during World War II they moved to Namangan. My mother had only four years of education—there was no time to study further, she needed to survive. She worked a lot and hard. I was already born in Namangan.

— Do you often return to the city of your childhood?

— Rarely. The last time was about 7 years ago. It's no longer the Namangan I grew up in: the canals where I swam are overgrown with slime, much has changed. Childhood was difficult, but it was precisely that which hardened me, taught me to live and survive. Like many boys of that time, I was raised by the street. The world is different now: we didn't have internet, computers, tablets—the street replaced all of that for us. Namangan for me is the city of my birth, first love, and losses: this is where I lost my mother when I was in eighth grade, and my grandmother.

— You've already mentioned your mother's difficult fate. What was she like?

— Strong and strict. She raised me with an "iron fist"—I knew what love was, but I also knew the belt and standing in the corner. After my mother's death, my sister Lena largely replaced her—she was 12 years older. We're still very close. My sister gave me a lot of warmth, strength, and belief in myself. She graduated from pedagogical institute and, as a future elementary school teacher, "experimented" on me: at four years old I was already reading and writing. I couldn't stand it, like any boy, but Lena was an excellent teacher.

— Did it help in life?

— No. Everything should be done in its own time. Nowadays parents often try to teach children too early—it's more about satisfying their own ambitions. In my case, the very first day of school turned out with me getting bored in class, packing my bag and going home, telling the teacher that I already knew all this. Until third grade I was an excellent student, until, upon becoming a Pioneer, I told my mother that I was an adult and wouldn't be an excellent student anymore. I kept my word: I became a good student, and from seventh grade I got some C's too. But I finished school well—we had wonderful teachers who prepared everyone for admission to their chosen university, and they "pulled me up" too.

About Mark Weil's pedagogy

— So you had already decided then to apply to theater institute?

— Yes, but the decision came only before finishing school. Before that I didn't dream of being an actor. But by fate's will I became a student at the Tashkent Theater and Art Institute named after A.N. Ostrovsky (now GIIKU named after Mannon Uygur) in Alexander Kuzin's course, and later transferred to Mark Yakovlevich Weil's course. Since 1991 I was accepted into the theater troupe and have been serving in it for over 30 years now.

— What kind of master was Mark Weil?

— A real one. Demanding, intelligent, subtle, able not to impose but to give the opportunity to learn yourself. Training was built flexibly, "here and now," for each student, not strictly according to a system. Vail graduated a whole generation of brilliant actors—Gleb Gollender, Muhammadiso Abdulkhairov, Lola Eltoeva, Karina Arutyunyan.

— Your first role on the Ilkhom stage?

— In the play "200 Years Have Passed," we, still students, played people from the future—perfect, devoid of sadness and melancholy. And the first leading role was Caligula in my diploma work based on A. Camus.

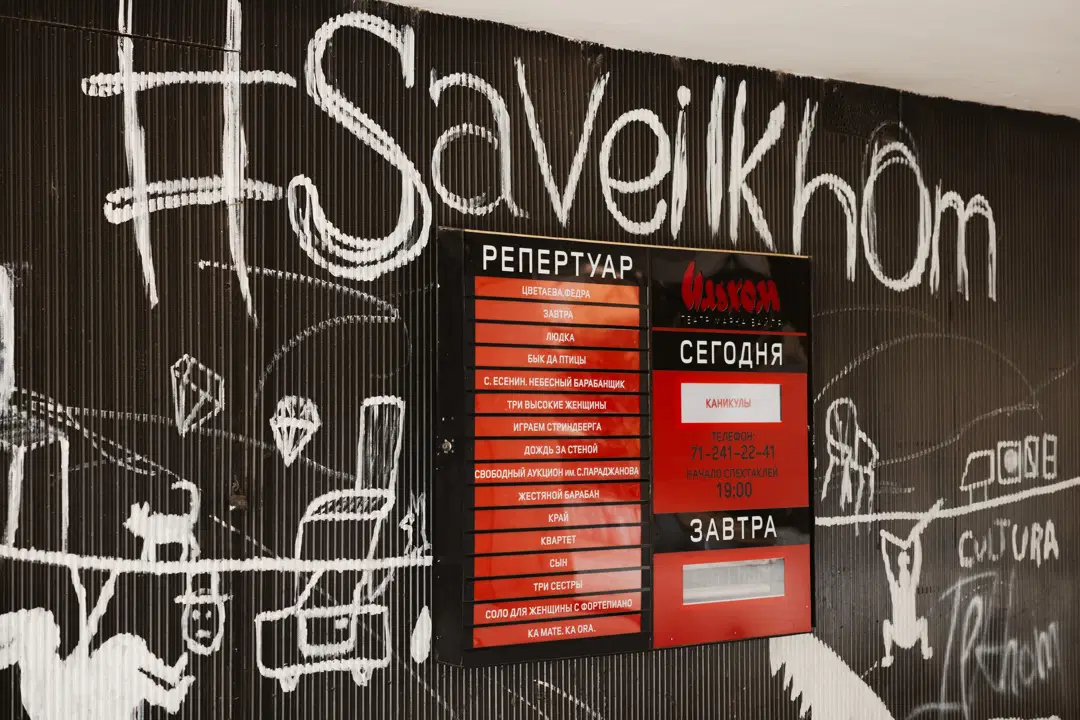

Photo: Alina Borisova / HD magazine

About prohibitions in art and his dislike of Hamlet

— Have many theater productions gone into oblivion?

— Of course. It's a natural living process. Theater isn't cinema, where everything is on film and remains in history forever. Theater is born here and now and is never repeatable. And each production has its own life and its own term.

— Are there productions you would like to restore?

— No. I tried several times to restore Bertolt Brecht's "A Respectable Wedding," staged by Mark Wail in the first years of the theater's existence and for many years considered its calling card, but I understood: we need to move forward. We shouldn't live in the past—it's important to create something new.

— In contemporary theater, quite bold reinterpretations of classical works happen very often.

— Theater is a separate art form. Literature here is simply a foundation from which something new is born. And when people are outraged: "How can you touch the classics?!"—I answer: you can and you must! When we turn classics into something "dusty," "museum-like"—that's terrible and wrong. Why can't I take Tolstoy and reinterpret him the way I feel? Here, today—in the 21st century, in 2025! Who forbids me from doing this?! There are no prohibitions in art at all! And there shouldn't be! Pushkin was a hooligan who rejected all rules.

— In one of his last interviews, People's Artist of the RSFSR Anatoly Romashin said that the dream role for an actor is Hamlet.

— Hamlet was never my favorite character! My hero is Cyrano de Bergerac. Yes, I don't have such a big nose, but that's not the point, but what's inside this person. And how subtly and painfully he feels the ugliness of this world, and how the world cannot forgive him for this. We're used to just seeing the "wrapper" and unable to see what's underneath. Mark Yakovlevich in the early 2000s staged a wonderful play "Rhinoceros" based on Eugène Ionesco's play—it was a student work of the second or third year of the Ilkhom theater studio. This play is precisely about how over time we seem to put on rhinoceros skin and stop feeling the most important things in this life.

— Do you remember how the collective met you at the beginning of your creative path? Were there attempts to "sideline" you, deprive you of roles?

— Ilkhom has a special atmosphere—it's precisely what helped the theater live a long and bright life. There's no concept of "sidelining" here.

The actor's profession is dependent: the director either sees you in the production or doesn't. And instead of complaining, it's better to think about why you're no longer being offered roles.

— Were you afraid of becoming hostage to one role?

— No.

— When did you first try yourself as a director?

— When I started teaching at the School of Dramatic Art at the theater. With students we made a sketch based on Mikhail Ugarov's play "Oblom off," which later became a diploma production and entered the theater's repertoire. This was my first directorial work under the close guidance of Mark Yakovlevich Weil.

— Have there been cases when a production remained misunderstood by the audience?

— Yes, and it's felt immediately. For example, Mark Yakovlevich Weil's wonderful production "ART" with Evgeny Dmitriev, Bernard Nazarmukhammedov, and Anton Pakhomov—it was beautiful, deep, but not fully accepted by the public. Or the production "The Castle K." based on F. Kafka directed by Maxim Fadeev: it was as if an invisible wall stood between stage and auditorium, and only a few found resonance. After the showing there was silence. But theater isn't a blockbuster where people go for popcorn. The audience must be prepared: know the director, author, understand the context. And even when you're ready, understanding doesn't always come. Theater is unpredictable.

Photo: Alina Borisova / HD magazine

— You worked with inclusive theater. Was it difficult?

— Not easy. It's a special world, and I'm grateful I could touch it. But I understood: you need to live this, give all your time, otherwise it would be dishonest. Therefore I bow down before Liliya Sevastyanova, who dedicated herself to inclusive theater.

— Can anyone dictate conditions to Ilkhom "from above"?

— No. And I state this categorically: no one "hands down" anything to Ilkhom. Mark Weil created a theater that would never serve any ideology. And this is the main commandment in art for us. Collaborating with the Goethe Institute, the European Union, or other organizations, we propose our own ideas and projects—no one tells us what and how to perform. Yes, they might approach us with a proposal to make, for example, an inclusive production, and we'll consider such a possibility. But promoting someone's ideology or staging "hurrah-patriotic" productions devoid of truth and our belief in them—that's not for us.

— A character in the film "Moscow Does Not Believe in Tears" claimed that with the advent of television, cinema, books, theater would disappear...

— Theater was and will be. It's a living art and a rare opportunity today for real communication. We've long been watching cinema at home, but you can't watch a performance that way. You leave home, meet people, experience a story together with them and discuss it—this is important for a person. Live theatrical art—be it opera, ballet, or drama—will remain despite everything.

— What are you working on now?

— We're preparing for the anniversary, 50th, theater season. There are many plans. Now rehearsals are underway for a project based on Konstantin Simonov's novella "20 Days Without War," where I'm rehearsing the role of Major Lopatin, which the great Yuri Nikulin performed in his time in Alexei German's film of the same name. The premiere is scheduled for the season opening—September 12, director Alexander Plotnikov. We're preparing a large exhibition dedicated to the theater's history. Together with the Foundation for Development of Culture and Art of Uzbekistan, we're working on an experimental theater project for the Uzbek pavilion at the Venice Biennale. In October, rehearsals will begin for a production dedicated to Mark Weil, based on Mikhail Bulgakov's play "Molière," where I'll already appear as director. We plan to time the premiere to the Master's birthday—January 25.

Photo: Alina Borisova / HD magazine

About film roles you wait for and those you walk away from

— Do you remember your first film role?

— Honestly, no. But I clearly remember the one after which I started being recognized at the Chorsu bazaar. It was the film "Kechir" ("Forgive"), where my partner was the wonderful singer Rayhon.

— Did recognition help?

— Differently. But it opened up an interesting side of people's psychology for me: if you're famous, appearing in films—it means you're rich, and they can "rip you off" more.

— Do you have favorite roles?

— I don't have many good films and roles. One of the few works I'm truly satisfied with is the film "Uncle." Rashid Karimovich Malikov was a very demanding director, and I'm comfortable with people who know exactly what they want and know how to demand.

— Are there themes or roles you consciously avoid?

— Such themes and roles haven't been offered yet, but they certainly exist. These are—propaganda of any kind of violence, war, murders, drugs.

— And have you refused roles?

— In cinema—yes, and often: boring, weak scripts, working with bad directors. In theater—no. I remember a case at Ilkhom: one production, which wasn't staged by Mark Yakovlevich Weil, I didn't like at all. One of the actors involved in it was leaving, and Mark Yakovlevich assigned me to this role. I tried to refuse, but he asked: "Are you an actor of the main ensemble? — Yes. — So, go and through 'don't want to' make the role become the most important and interesting for you." In theater you don't work—you serve.

— Do you often rewatch films with your participation?

— Rarely. Sometimes you bet on a picture, but in the process you understand—this isn't it. Then you don't even go to the premiere. For example, the film "101." The story of one hundred and one Uzbek prisoners of war is itself very important and significant for us—good cinema could have come from it. But in the end everything turned out frivolous. Initially it was planned to shoot a 15-minute trailer-application, but the producers decided to make a full-length film from the shot material. At the same time, preparation was superficial, filming took only 20 days.

Photo: Alina Borisova / HD magazine

— And which film are you satisfied with?

— Not one! I have a complicated relationship with cinema. I give more of myself to theater, although I would like to play something big and real in cinema too. I don't have a dream role, but there are directors I would dream of working with: Wes Anderson ("Moonrise Kingdom," "The Grand Budapest Hotel")—I adore his aesthetics, Quentin Tarantino, Andrey Zvyagintsev. And among actors I really love Al Pacino: I learned a lot watching his work. In theater, of course—Mikhail Kaminsky, who left this world not long ago. He was an outstanding actor. Among Russian actors—Oleg Yankovsky.

About the Master, his death, and the burden of responsibility

— September 2007. How did you learn about Mark Weil's death?

— It happened on September 6, on the eve of the 32nd season opening. We parted late in the evening after rehearsal of Aeschylus's "Oresteia." 40 minutes after parting, I got a call: Mark Yakovlevich was stabbed in the entrance hall. At first there was hope—he was alive, they were taking him in an ambulance. But at the gates of the 16th hospital we were told he died. The feeling is like you're falling into a funnel, and everything is collapsing: what you lived for, what you lived for the sake of.

— How did you become the theater's artistic director?

— No one knew what to do next. We decided—we need to preserve the theater created by the Master. There was no initiative on my part to become artistic director—I was chosen. This is enormous responsibility—to head a legendary theater with rich history. At first it was very hard, I wanted to run away. And now sometimes I also want to drop everything and run.

Photo: Alina Borisova / HD magazine

— Are there rules at Ilkhom?

— Like in any system, there are unspoken laws here. The main thing is to remain human and love this place. If you don't love it—leave. It's important to feel that this is your space, without which you cannot be. At Ilkhom work those who understand: they cannot exist without this theater. I always tell students: "If you can live without this profession—live!" Fanaticism is needed here: going on stage should be a vital necessity. It's not about fame and money, but about internal need. Today many go to theater university for "quick" popularity—to get into cinema faster and start earning at weddings. Such is the reality: they pay little in theater, in cinema too, and the main earnings are at celebrations. To be invited there, you need to be recognizable on screen. This is how the survival chain of the Uzbek artist is built.

About stage fright and self-censorship

— At the beginning of your career, were you afraid of the stage?

— I was afraid and I'm still afraid. Over the years, the fear only intensifies because responsibility grows. A young person is allowed to make mistakes, but when an experienced actor with a name comes on stage, people look at them differently—they expect perfection. Yes, I also have the right to make mistakes, but I understand that today students and colleagues look up to me, and this obliges.

— Were there roles that helped overcome fear?

— Each role is a step forward, even if it's unsuccessful. This is not so much professional as internal success. Failures happen to everyone, even to the great. The main thing is that there are victories between them, otherwise you'll break.

— What about creative crises?

— Of course they happen. Sometimes it seems you need to leave the profession: two unsuccessful productions in a row—and you already lose the taste for life, stop loving yourself. Today you have Ilkhom and talent, tomorrow everything can change. I see this in students too: someone brightly lights up and quickly fades, and someone reveals themselves only after years. The reasons for these changes aren't fully clear. But it's impossible to quit. A creative profession is a disease, but a disease you don't want to recover from. Television, cinema, theater—all of this draws you in so that, despite difficulties, you remain in this world and consider yourself happy to live precisely here.

— Can someone become an actor at any age?

— Yes, age is not a barrier. I have students who are thirty-eight and forty years old. It's rare, but I felt they had the right to this, and I didn't regret my decision. However, it's harder for an adult to break habitual attitudes—and in theater school you can't do without this. You need to "remove the skin" of the rhinoceros, bare yourself internally and spiritually. Age itself doesn't interfere, but life experience is necessary for an actor: in youth, temperament, charm, and naivety save you; later—only accumulated years and experiences.

Photo: Alina Borisova / HD magazine

— Do you have self-censorship?

— Of course. It manifests in my understanding of the world, in my commandments and "stops." There's a line that cannot be crossed, but if the artistic task justifies it, I'm ready to go far.

— How would you characterize the Ilkhom theater audience?

— Our audience is the intelligentsia, students, diplomats. It's a thinking, feeling, reasoning person, and they have no age or nationality.

— What do you hear more often—praise or criticism?

— Both. Ilkhom is either loved or can't be tolerated. There are no indifferent people—and that's the main thing. There's harsh criticism too, but there are still more positive reviews.

— How do you relate to statements addressed to you?

— Calmly. This is a public profession, and you need to be ready for any opinion and assessment addressed to you. It's impossible to please everyone—that would be strange and even suspicious. Different people—different tastes, and that's normal.

About stalkers and inhumane treatment of animals

— What does Boris Gafurov do for hobbies and how does he rest?

— I swim, go to the pool, study swimming technique. This is my meditation, this is my physical exercise. I understood that water is my element. I also love walking with my family and dog.

— Since we're talking about animals... On your social media page there are announcements about charity, about helping animals. Are there results?

— Not only I deal with animals, their placement and rescue, but the whole theater and my whole family. I love animals very much. And this is my painful topic. How animals are treated in Uzbekistan, I consider unacceptable and immoral. Walking with my dog, I observe how people react to it—and it's terrible. As for results, they're small, but they exist.

Happiness according to Boris Gafurov

— If at the beginning of your career you met yourself, what advice would you give yourself?

— Live and enjoy: get pleasure from life, from the profession, from every minute and cherish those dear to you.

— And to your students?

— The same thing—learn to live here and now, get pleasure from life, from the profession, from everything. Be patient on the path to your goal and bear responsibility for your actions.

— The great actor Lev Durov said that after a premiere any actor, any director feels as if they just gave birth to a child—and it was taken away from them. Is there such a feeling?

— Close, close to this. It's always emptiness, loss. But pleasant emptiness. Then comes a moment when euphoria passes, and the eternal question arises: what's next?

— Conduct a comparative analysis: Boris Gafurov at the beginning of his creative path and today. What has changed?

— Difficult question. Everything has changed: ears stopped being protruding, gray hair appeared. There's more responsibility and fears.

— But how do you want to remain in the audience's memory?

— Just like this, as I am now.

— What can you never forgive?

— I can forgive a lot, except lies and betrayal.

— What advice from Mark Weil is still vital for you, what do you continue to follow?

— Being able to conquer your fear—that's first. If fear begins to control you, you stop being an artist. Second—not adhering to any ideology, going the path of your own truth, your own understanding of life. All of this is probably the simplest and most important. And also: whatever happens in life, continue to honestly do your work. Just get up, go and do, do.

— What is happiness for you?

— Understanding of happiness changes with years and experience. Now happiness for me is everything my life consists of. I just really want all wars to stop.