How Ural Cossacks Ended Up in Karakalpakstan

In 1874, a rebellion of Old Believer Cossacks erupted in the Urals. The cause was a decree by Emperor Alexander II requiring every Yaik (Ural) Cossack to serve continuously in the military, wear uniforms, and maintain horses and weapons. The Uralians, accustomed to living by fishing and hunting, refused to obey the new orders, considering them a ruinous encroachment on traditional Cossack freedoms.

After suppressing the unrest, about 2,500 Uralians were stripped of their Cossack status and exiled to Turkestan. At first only men were deported, but in 1877–1878, more than 750 families were forcibly relocated to join them. Husbands and wives, separated for years, often didn't recognize each other. The exiles suffered from hunger and disease; some even threw themselves overboard from steamboats transporting them along the Amu Darya River.

Under Emperor Alexander III, heir to Alexander II, the Uralians exiled to Turkestan were permitted to return home and regain their Cossack status. Not everyone took advantage of this imperial mercy: only about 850 people returned from Turkestan, while the rest remained where they'd been sent.

The tsarist authorities expected them to help "develop" the conquered territories—just as had happened in the Urals and Siberia. They were settled in the Amu Darya delta, closer to the border with Khiva—the last of Russia's Turkestan possessions to be conquered. Near the Petro-Alexandrovsk fortress (now Turtkul), the Uralians founded the settlement of Pervonachalny ("Original").

Later, other Cossack settlements appeared: a sloboda (settlement) in Turtkul itself, a Ural settlement near Nukus, Zair and Kazak-Darya, Ak-Darya, Kyzyl-Zhar. Over time they reached the shores of the Aral Sea, where they established fishing operations—in Uchsai, Urga, and Porlytau. Cossack settlements even appeared in Muynak and Kungrad.

Thus on the empire's periphery arose a unique community of Ural Old Believer Cossacks. They came to be called ukhodtsy—"those who left"—people who departed from their former life but remained themselves.

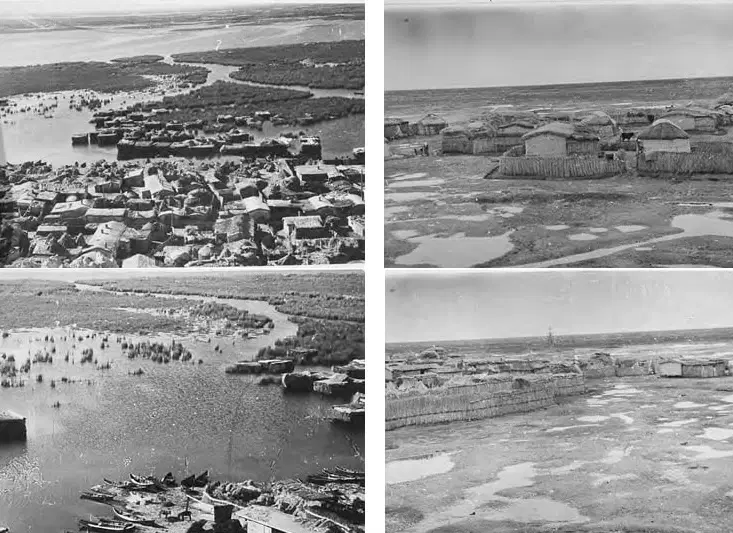

This is how these places looked in photographs from the early 1950s.

A Mother Superior with the Rank of Major

A century and a half later, HD magazine traveled to Karakalpakstan to find the Uralians' descendants and tell their story. Over 150 years, their community—judging by the original number of exiled Cossacks—has shrunk by roughly a hundredfold.

Now in northern Karakalpakstan—in Nukus, at Pristan, in Kungrad and Takhiatash—only 20–25 Uralian families remain, predominantly elderly. A few younger families live in Beruni and Turtkul.

The focal point of their small community is a modest prayer house on the outskirts of Nukus, which holds Old Believer icons, prayer books, and relics. The Ural Cossacks historically grew through peasant Old Believers who fled Central Russia after the Orthodox schism in the 17th century, so Old Belief is a crucial part of the ukhodtsy descendants' cultural code.

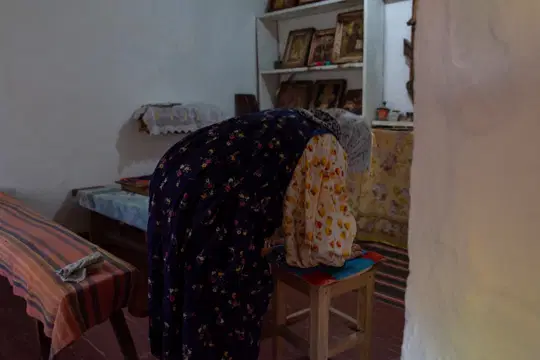

The Old Believer prayer house is hidden behind a reed fence. Inside it's not particularly spacious, but there are benches and stools—elderly parishioners lean on them during prayers.

The prayer house in Nukus can't be called either a church or a chapel—unlike canonical Orthodoxy, the Aral region's Old Believers got by without priests. Until recently, services were led by a *nastavnik* (spiritual leader, called "grandfather" in the Uralians' dialect) named Savin. After his death in 2016, seniority in the community passed to "grandmother" Olga Kiseleva, who calls herself Matrena.

"Grandmother" Matrena is a former traffic police officer with the rank of major. Her police past reveals itself only in her attitude toward her "ataman's" (chieftain's) mission: you can't just up and abandon your post, you can't leave a community that depends on your efforts.

"If I leave, everything here will end, because so far there's no one visible to continue. People are begging me by Christ and God not to leave, not to abandon them," she says.

Olga Kiselyova, who is called Matryona here.

After the USSR's collapse, many Uralians—mainly young and able-bodied—began returning to Russia's Volgograd and Astrakhan oblasts, where the climate and nature resemble the lower Amu Darya. Matrena herself sadly admits: the youth are "already different—not like we were." Those who left for Russia and joined local Old Believer communities still hold onto the faith: there are churches there, spiritual leaders, observance of rituals. Here, on the desolate Karakalpak land, the old faith is sustained by those who still remember.

Matrena and her husband show the antique icons, crosses, and books stored in the prayer house. "Many bring icons and books for safekeeping. Sometimes when people leave, they leave them here so they won't be lost," she says.

"All our rituals happen here: baptisms, weddings, funerals. Our icons, as they say, were gathered bit by bit—everyone brought what they could. We live, help each other, and remember who we are," her husband adds.

Old Believer icons are considered cultural treasures and are prohibited from export from Uzbekistan.

Matrena's husband calls the Uralians Russian more from habit, and speaks of Russia as culturally close but still a separate country:

"I've traveled a lot in my life: with my father for work, and on my own. I've lived in Russia and the Caucasus, but I always came back here. This is our land, our homeland—I was born here, my parents lived here, this is my home."

Uralians on the Aral

Both now and 150 years ago, the Aral region's deserts differed from the conditions the exiled Cossacks were accustomed to in the Urals. Initially, the Ural Cossacks exiled to Turkestan kept to themselves: they established settlements where no people lived. The languages and customs of Kazakhs, Karakalpaks, and Turkmens were alien to them, so interaction was limited to barter and trade.

Having settled into their new home, the Uralians returned to the craft they'd practiced back in their native places.

Eyewitnesses from the late 19th century write that the Amu Darya teemed with fish—sturgeon, stellate sturgeon, sterlet. By this time, in Muynak and at other fisheries near lakes and channels, the Uralians had organized large fishing artels (cooperatives). The Uralian community leased land plots from the Karakalpaks—paying rent in fish or money.

Some Cossacks took up gardening and farming in the Amu Darya valley. True, they didn't achieve great success in this—not everyone knew how to work the land. Over time they learned from locals to grow cotton, rice, and sesame—nothing like this grew in the Urals. Their farms gradually acquired not only familiar horses but also camels and donkeys.

An entire infrastructure grew around the fisheries: carpenters and blacksmiths built flat-bottomed boats for navigating shallow river channels, repaired tools, wove nets. They made barrels for salting fish and caviar, which was then exported to Russia.

Only ruins remained from the artel crafts of the Aral Sea region.

Soon points of contact with the local population emerged. The Cossacks were known for their industriousness: they built houses, dug irrigation canals (aryks), caught fish "Russian-style"—that is, with nets—a method the Karakalpaks adopted from them. The Uralians, in turn, learned from their neighbors to survive in the desert, find water, and use camels in their households. Unique borrowings appeared in their speech, new skills in everyday life.

When a Neighbor is Closer Than Kin

"Our neighbors are wonderful," says Matrena. "At Easter I baked buns, dyed eggs—brought them to all the neighbors... Before, children would run around the yard shouting 'Christ is risen!' and we'd give them Easter cakes and painted eggs. People greet each other, respect each other."

The Uralians' descendants say that good neighborly relations with Karakalpaks aren't just a slogan from friendship-of-peoples posters. Next to Matrena lives a mullah—he and other Karakalpak neighbors keep watch to ensure strangers don't approach the prayer house.

"Grandmother" Matrena lives next door to a mosque. One of her neighbors is the local imam.

These precautions didn't arise for nothing. Matrena told how forty years ago their old prayer house was robbed—all the valuable icons were stolen.

"It was a blow, of course. The icons were eventually found—already in Crimea, discovered at one of the dioceses. We couldn't get them returned here—we were afraid history would repeat itself," she recalls.

The culprits were found (it turned out young Old Believers had sold the icons) and punished. How exactly they were punished, the retired police major doesn't say. And she adds:

"In the past, if children didn't observe Old Believer canons, parents asked to be buried together with books and icons. Many disappeared that way."

Old Believer faith influenced daily life. For example, tobacco smoking was considered a grave sin; drinking tea and eating garlic were forbidden. Even in the 1970s–80s, elders consumed only herbal infusions or hot water instead of tea. They fried or dried fish, and strictly observed numerous fasts. At memorial services they used only wooden utensils: metal was considered "unclean."

Now the ban on drinking tea is no longer valid.

The "Ukhodtsy" Are Departing to Heaven

The Old Believer traditions observed by the exiled Uralians are gradually receding into the past. For example, there's no longer a strict ban on mixed marriages with people of other nationalities and faiths.

"Of course it would be better with our own, but what can you do?" Matrena sighs. "Parishioners come and say: the granddaughters have grown up, but there are no grooms around. They marry Karakalpaks, Uzbeks, Kazakhs. They live well: some for love, some were 'stolen' as used to happen. But what can you do? The main thing is to preserve the family, respect for each other."

Some Uralians, having lived their lives in mixed families, themselves bequeath to be buried according to Islamic customs. In the community it's customary to respect and fulfill the last will.

The cemetery where the Old Believers were buried has long been abandoned.

The Cossack settlements on the Amu Darya have emptied, the sea that fed Karakalpaks, Kazakhs, and Uralians has dried up, the fishing artels remain only in the elders' memories. But as long as "grandmother" Matrena opens the prayer house and lights the icon lamps, the Old Believer community of Karakalpakstan lives on.

She herself doesn't lose heart and isn't planning to leave the Aral region:

"To be honest, I don't want to leave. I'll visit my children on vacation, then come back. Otherwise—this land is my home, everything here is mine. As long as I have strength, as long as my legs carry me—I'll manage on my own."