The aesthetics of the 2000s—a synthesis of abundance and counterculture—now seem so distant and alluring. It would not be an exaggeration to say that it was the 2000s that shaped more than one generation and set a cultural vector that remains relevant to this day, evoking warm nostalgic feelings even in those who did not experience that era.

But what is happening with this culture in Uzbekistan today? Behind the ideas of street dance from iconic films, there is a vibrant community that survives, grows, and fights for its place in the cultural space of the city.

A bit of basics

Most modern street styles in Tashkent are descendants of street dance, which originated in the USA in the seventies and nineties: economic crisis, racial segregation, lack of prospects—all this created an environment where young people sought an outlet for their energy and even anger. These styles developed on the streets, in clubs, at block parties, and at hip-hop events. They are united by freestyle culture, that is, movements created improvisationally. Today, three key styles can be distinguished: athletic breaking (breaking), groovy hip-hop (freestyle hip-hop), and muscle control-based popping (popping).

However, we’d better leave the history of the dance scene to the theorists, because in street dance, the key has always been the community, not the school.

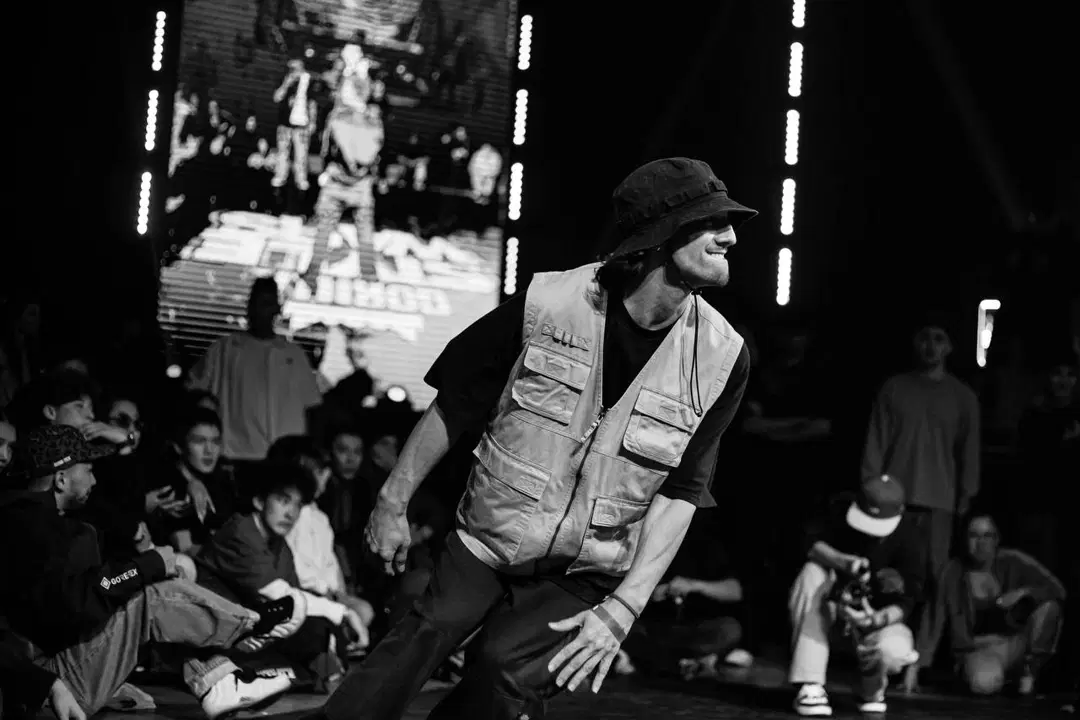

On December 20, the annual Unity Base battle took place in Tashkent. We decided that this was a great reason to ask some questions: what is the street dance scene in Tashkent like? How did the community form? What challenges do they face? We spoke with the founder of the Unity Base studio, Tima Unity, professional dancer and breaking athlete Dmitry Lukashev, creative figure and professional dancer Arthur Sadriyev (ARTHUR OVERHITZ) and the founder of the Overhitz crew, Vladimir Meshcheryakov.

Why street dance is art

Street dancing is often considered more of a teenage, temporary, unstable thing: "Street dancing was perceived with skepticism for a long time—like everything new that people haven't had a chance to figure out yet," says Dmitry Lukashev.

Partly this is due to the very nature of freestyle—it has a form that is unusual for the viewer, which does not always look like a “finished work of art.” However, within the culture, freestyle is a certain improvisational algorithm, a special way of thinking and interacting with music. The dancer interprets the music in real time: the rhythm, pauses, structure of the track, and their own emotional state. It is a language without memorized text, but with its own grammar, dialogues, and accents. Tima Unity (also known as MC Fromunity at local battles) –– one of the organizers of battles in Tashkent):

Freestyle comes in different forms and it really isn't always art. Freestyle is about the moment and the feeling. For example, choreographing in street dance styles or editing into a beautiful video — that's art. There are many different branches in street dance, and all of this is more about culture. And even this word is shortened to the word "subculture."

Tima Unity

Thus, in street dance, the art is not freestyle itself as a form, but the ability of dance to go beyond the exclusivity of improvisation and turn into an expression, a performance. In these cases, movement becomes a way to speak about personal experience and inner states without resorting to words.

This feature is pointed out by the creative artist and professional dancer Artur Sadriyev (ARTHUR OVERHITZ):

Through dance, we are able to convey emotions—important first and foremost to the dancer themselves—in which others can find their own meaning. These are feelings that, for various reasons, cannot be expressed in words. But we also cannot “keep silent” about them. By dancing, we tell stories. We speak of pain and joy, sadness and love, of inner states that are difficult to explain directly. In our craft, it’s not only the body that matters. Gestures, facial expressions, pauses, and small details are important too.

Artur Sadriev

The question of the value of street dance for culture is still being raised—especially in circles where it is accustomed to being seen as entertainment or a temporary trend:

Are street dances valuable for culture? I can confidently say yes, because dance has shown tremendous progress since its development, and has made it clear that it has a great future! Street dances have given people freedom, a sense of rhythm, an awareness of themselves in space, and the opportunity to create. People who practice dance have become physically stronger and more flexible.

Dmitry Lukashev

To understand the scale of street dance today, it is important to go beyond a local perspective and look at how this culture exists in a global context:

Street dance is an entire culture with its own branches (MCs, DJs, dancers, artists whose music we dance to). Many artists have their own theatrical productions, which take place in famous theaters in Europe, Japan, and Russia. In many countries, dance has already become an integral part of the culture: for example, in Japan, the government actively supports breaking, and major brands also provide support: Nike, G-Shock, Casio, Adidas, Mercedes Benz, Red Bull, etc. As a result, more and more ordinary people are becoming interested in and gladly supporting dance culture.

Dmitry Lukashev

The distinctive feature of street dances has always been not only their unique movement techniques, but also the environment in which they exist. These styles were born from live human interaction. Gradually, a community was formed, and it is from this environment that the battle naturally emerges—not as a competition, but as a form of communication within the culture.

Battle is the heart of street dance culture. Although the word "battle" literally translates as fight, in street dance culture a battle originally served the opposite function, reducing the level of real conflict.

Dance allowed people to release tension without breaking the connection between them. That is why, after every performance, dancers often shake hands or hug each other.

There is no fixed hierarchy here. In a battle, even the most famous dancer can lose, and that's what makes it democratic. Reputation does not guarantee victory here, and respect must be earned anew each time. This creates a situation rare for social structures: status is not fixed, but fluid, just like the dance itself. Such a system does not divide, but keeps people together.

The key element of a battle is the circle. It unites both physically and symbolically. Unlike a stage, there is no distance here between the participant and the audience: anyone can become part of the action. You may not dance, but you are already inside the process, you are a witness and a participant, and for newcomers, the battle is an entry into the community.

Common language and mutual recognition

Battles create a common language. Dancers learn to read each other's movements, respond to them, respect the opponent's musicality and style. Even when styles are different, the very fact of participation means recognition. This is especially important in multicultural and multigenerational communities. Battles erase boundaries—between countries, schools, generations.

You can see how the idea of battles was implemented in the example of the Tashkent project Unity Base.

Unity Base: point of unification

The annual Unity Base battle is one of the few events that brings together street dancers from different styles and schools. The project did not appear immediately and did not follow a classic scenario. The path to its creation was not easy.

It all began long before the name Unity Base appeared — in a small hall and a large community that was already searching for points of connection.

When we — freestyle dancers (potential future and current battlers) — were starting out, there were about 300 of us (in all the schools combined, but at most 200 of us actually danced at battles), and we somehow managed to fit this whole crowd into our modest 100-square-meter hall. There was always little space, but you can't even imagine the kind of energy that filled those four walls.

Tima Unity

It was precisely this sense of belonging, shared energy, and lively exchange that later formed the basis of the project's idea—a space where the unification of people around dance is of primary importance.

Tima Unity ended up in the industry almost by accident, having invested in his dancer friends' dream to open a studio. When the partnership fell apart, he was left with an unfinished project.

“I had absolutely no idea what to do with it, but I had to at least cover the cost of the studio repairs. I wasn't a teacher or a choreographer — it all started for me as a gamble and faith in other people,” says Tima Unity.

The idea to hold battles appeared even before the official opening of the studio. At that time, there was fierce competition between schools in Tashkent, and events held at someone else's venue were often ignored.

We wanted to create a place where everyone would forget whose territory it was. That’s how the name Unity Base came about—a base, a point of unification. We didn’t have our own groups or dancers, and we believed that’s exactly why people would come to us.

Tima Unity

Small Land: a scene in conditions of scarcity

The context in which the dance community of Uzbekistan exists is far from ideal. Despite its inner depth and expressiveness, street dance is rarely perceived with respect outside the community itself. For the general public, it still remains something marginal or unserious—and this is exactly what dancers in Uzbekistan face.

As Vladimir Meshcheryakov — hip-hop dancer, Gorilla Energy Pro Team athlete, and founder of the Overhitz crew — notes, street dances face systemic challenges.

For the public, we are a culture that is still not understood. When we try to raise our flag abroad, our government is not particularly interested in this, and in a certain way, it is even disapproved of.

Vladimir Meshcheryakov

According to Vladimir's estimates, the active core — those who live the culture, travel, and develop it — is only 50-60 people across the entire country. There are hundreds of students, but the main group is very small.

The economic factor also adds to the challenges. The usual cooperation with brands in the West is a rarity here. “Brands are not ready to work with dancers this way. They look at followers, reach, not at the quality of the dance,” — Vladimir Meshcheryakov. Dancers find it difficult not only to get work, but also to find a place for the full development of their projects.

Community building and encountered challenges

Dancer and breaking athlete Dmitry Lukashev (Bboy Lookout) notes that the development of hip-hop culture today is moving in two directions.

On one hand, there are experienced dancers who have been in the industry for many years, travel abroad, participate in battles and master classes from world leaders of the scene. In his opinion, it is they who set the benchmark for the youth, demonstrating personal growth and passing on their knowledge further.

On the other hand, there are children and teenagers who are just entering the culture through training, basics, and local battles. Their development directly depends on the number of jams and events, which are still not so many in Uzbekistan.

At the same time, Dmitry also points out a problem within the scene — the tendency of certain coaches and teams to isolate themselves from the broader community:

There is also a dark side to development. Many try to distance themselves and train somewhere in their own gym, away from the rest of the community. These divisions slow down progress, because the ideas that such coaches give to their children are the same detachment. Yet growth is possible precisely through communication and exchange, not through isolation.

Dmitry Lukashev

Arthur Sadriyev (ARTHUR OVERHITZ) believes that the street dance scene is developing slowly but steadily. According to him, the community has become more united, battles are being held more frequently, however, there is still a lack of international judges, and this issue still needs to be addressed:

The difficulty lies in the fact that funds are needed for development—classes and trips, which not everyone can earn through dancing. Growth happens not only through battles. It is essential to attend master classes and travel abroad—to the CIS, Europe, China—to see what level exists outside of home. We also rely on regular and productive training sessions.

Artur Sadriev

How to survive, grow, and why it is necessary to expand your geography

There is no academic system in street dance. Despite the challenges, the community finds its own unique recipes for growth.

One of the most fundamental criteria for a dancer's growth is traveling. But not as a tourist, rather by attending battles, master classes, and exchanging experiences with people. It is a window to the world, a source of new knowledge and motivation.

Vladimir Meshcheryakov

The second point to highlight is teaching:“When you start sharing information, you ‘empty yourself,’ making room for new knowledge. The cycle of ‘learn — share — learn again’ becomes the engine of personal and professional growth,” he explains.

The third key is development in related fields. Many dancers start DJing, drawing, or delve deeper into music, which enriches their dance.

A dancer is an instrument. And the better they are "tuned" and the more versatile they are, the more interesting their "sound" becomes.

Vladimir Meshcheryakov

Finally, the fourth key is the dancer's perseverance and mindset.

If you are ready after a loss to return to the gym with even more determination to prove that you can do better — then you will achieve your goal.

Dmitry Lukashev

Talking about himself, Bboy Lookout emphasizes that he has been practicing breaking for over 11 years, during which he has managed to win numerous battles, train young dancers, and represent Uzbekistan on the international stage. His main goal is to prove that a dancer from Uzbekistan can be competitive at the global level and to pass this path on to the next generation:

I come from a simple family and have encountered conversations like: "Well, these dances of yours are not serious at all," but I have traveled half the world thanks to dancing, and now my mom looks at what I do with pride.

Dmitry Lukashev

According to Dmitry Lukashev, street dance has evolved into a full-fledged cultural form with international recognition. He notes that the inclusion of breaking as a sports discipline became an important milestone, allowing for a balance between artistic expression and competitive format.

Breaking has recently been included as a sports discipline (it is in this field that art and sport are perfectly balanced). For example, major championships are held in Japan, and champions in this field compete all over the world, with the whole country cheering for their representatives. Russia, in turn, provides significant benefits for champions of the breaking scene when entering higher education institutions, and major sponsors such as (Gazprom, Lukoil, etc.) invest huge amounts of money in organizing high-quality competitions in this discipline. China has been a revelation in recent years in terms of Breaking. Over the past few years, China has nurtured and raised a huge number of street dance representatives; everything mentioned above about other countries is also practiced in China, where growth in recent years has reached almost 600%. I may be mistaken in the percentage, but I have no doubt about the number of new people in the community—they are making noise all over the world, and China actively supports its champions!

Dmitry Lukashev

The Future: Between TikTok and Tradition

The Unity team raises an important issue in freestyle right now: due to the pursuit of media exposure and TikTok culture, the ease and spontaneity that street dances are known for are being replaced by calculated trendy moves.

Why did it happen that from a big family we turned into small communities—is a separate topic, connected with the spirit of the times. Back then, life, people, and the atmosphere among the youth were different. Today, it’s more about TikToks and Reels, so it’s not really about the freestyle community anymore. Now it’s more of a numbers game, where improvisation doesn’t work and there’s a ready-made template everyone has to follow. After that, it’s judged by who sold it in a prettier package and whose looks more appealing and marketable.

Tima Unity

Culture is under pressure from a new reality. The essence of today's choice lies in this confrontation. The community is trying to preserve authenticity in a world that favors the fast and the media-savvy.

What does this challenging journey ultimately give?

Dancing gave me the opportunity for self-expression, communication skills, and physical strength. I represented Uzbekistan, traveled to different corners of the planet, and I believe that this is more than enough to love my craft with all my heart.

Dmitry Lukashev

The ability to not be afraid to break the rules, to move against the current. And for me, it is important that people understand what I want to convey with my dance, so that it is not just a set of movements, but meaning.

Vladimir Meshcheryakov