Tashkent, the City of Bread

The famine, devastation, and collapse of trade that Central Russia faced after the October Revolution of 1917 and the ensuing civil war transformed distant Asia into a dream of earthly paradise. "Tashkent, the City of Bread"—this was the title of a 1923 novella by writer Alexander Neverov. Its protagonist, 12-year-old Mishka Dodonov, leaves his Volga River village and sets out for Tashkent to earn grain through physical labor that will feed his starving family.

From neighbors he'd heard that you could get there by train. After countless adventures, he reaches the fairy-tale city:

"Past the gardens rolled marvelous, unseen carts (arbas) on two enormous wheels. Well-fed horses with ribbons in their tails and manes jingled bells. From baskets, from wooden boxes peeked various apples and something else, some berries with black and green clusters, wide white flatbreads. 'This is how they live!' thought Mishka, licking his dry, hungry lips."

«Tashkent, the City of Bread» (fragment of the cover of Alexander Neverov's publication).

The black market literally overwhelmed Russia at the time: caravans of meshochniki (bagmen—traders who traveled with sacks of goods) moved to the more prosperous south, to Asia and back. According to a report from the USSR People's Commissariat of Food, up to 60% of products reached the population precisely this way, at prices unregulated by the state.

The food crisis was overcome only with NEP—the New Economic Policy of the Bolsheviks, which permitted the private sector in trade and the food industry. Like mushrooms after rain, private restaurants appeared in the capitals and major cities, and market trade flourished. Shipments of flour, rice, and vegetables from Soviet Central Asia helped overcome their shortage in the country's center.

Plov Enters Public Dining

By the end of the 1920s, life in the Soviet Union was gradually stabilizing. Vivid evidence of this was the appearance of cookbooks. In the first post-revolutionary decade, mainly manuals on preparing pancakes from potato peelings or rationally using beet tops were published.

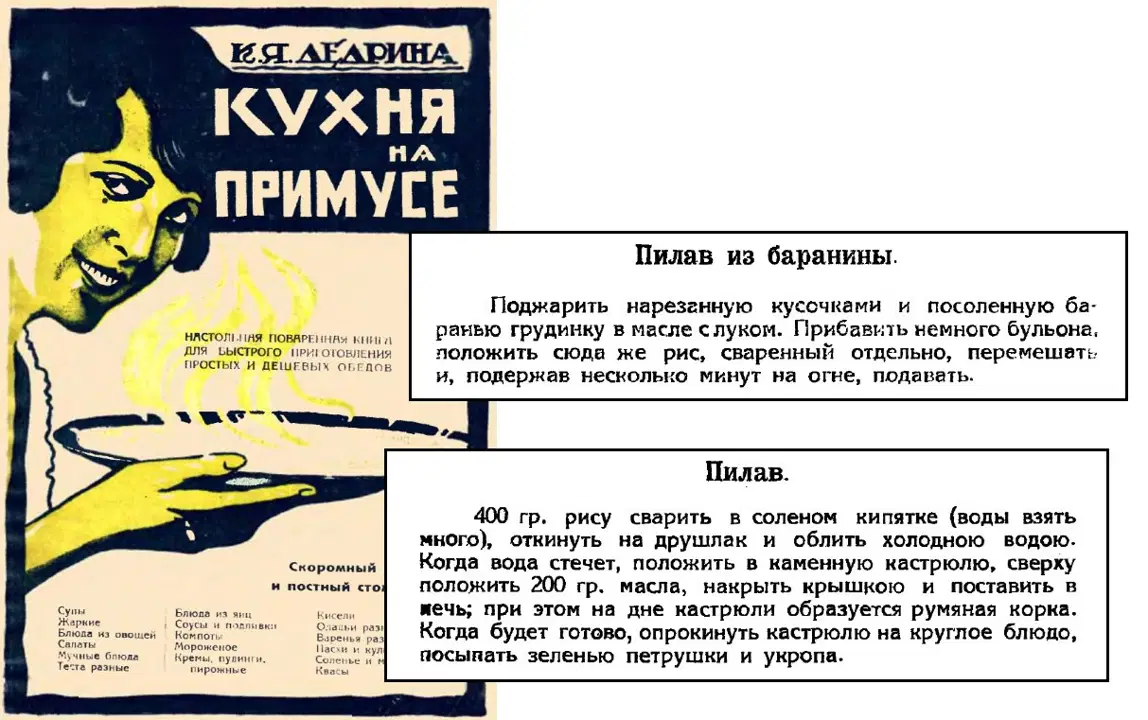

But already in 1927, for example, Katerina Dedrina's work "Kitchen on Stove and Primus" was published. Like no other, it reflected the transitional nature of the times. In content, the book already departed from the dreary stylistics of war communism, aimed not so much at cooking as at simple satiation with anything at all. Yet at the same time, it clearly bore the imprint of those difficult times.

Surprisingly, it even included "Asian pilav" (plov). Though its recipes were very conditional and primitive, it turns out the general public was already familiar with this dish.

Changes were also occurring in public dining. From the second half of the 1920s, Russia began creating fabriki-kukhni (factory-kitchens)—enormous enterprises capable of feeding several thousand workers and employees per day. Everything there was new and progressive for that time: from clean tables with white tablecloths to metal kitchen equipment—cauldrons, ovens, dishwashers. Production automation required unified recipes that combined benefit with economy.

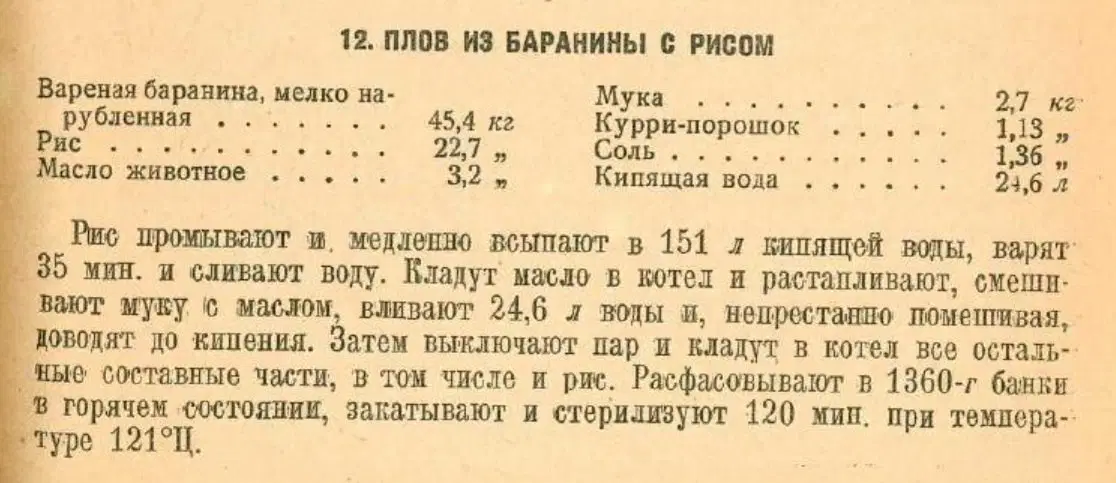

In response, "Recipe Collections for Public Dining Enterprises" appeared. They were republished in various versions throughout the entire socialist period, but the first such collection came out in 1937. In it, we already encounter the indispensable "plov with mutton." That is, this dish had already entered the menu of public dining establishments from Minsk to Vladivostok.

Let's not forget that collectivization gradually reached the kishlaks (villages) and auls (settlements) of Soviet Central Asia as well. Collective farms and state farms were created everywhere, meaning that harvested produce went not only to the nearest bazaar but also to Central Russia. Melons, dried fruits, rice—all of this became familiar to the population of the European part of the USSR.

The New Soviet Cuisine

The 1939 publication of the first edition of "The Book of Tasty and Healthy Food" became a kind of report on the creation of a new Soviet cuisine. Its appearance was a striking experiment, a sort of face of reforms conducted under the leadership of People's Commissar of the Food Industry Anastas Mikoyan.

The book became an amazing combination of pre-revolutionary tradition with a contemporary (for that time) understanding of healthy cuisine. One can argue at length about the predominance of public dining standards in it, about excessive calorie and carbohydrate counting, but no one can say that the dishes and eating manner in the 1939 book were backward, "sovok" (a derogatory term for Soviet-era mediocrity), or inconsistent with world trends. Moreover, an amazing collective of scientists formed around the writing of this book, who for many subsequent years headed the directions of nutrition and dietetics in Soviet science.

And what about Central Asian cuisine there? You won't believe it! It has an entire section titled "Plovs," which included plov with mutton, with fish, with pumpkin and fruits, and even plov with mushrooms.

The book was more oriented toward housewives. By the way, not only recipes could come to their aid, but also canned goods in stores. The "Reference Book of Uniform Wholesale and Retail Prices for Food Products in Moscow" for 1937, among many products, contains canned... plov. "Eastern plov" was packaged in cans weighing 350 and 370 grams for stores or 1.36 kg for public dining—for orders from military, geologists, etc.

Here, of course, we should note a characteristic feature of those years—interest in Eastern cuisine. Partly it was determined by the national factor: many members of Soviet leadership were from Transcaucasia. Dishes familiar to them gradually migrated from Kremlin receptions to the menus of good restaurants, and from there spread throughout the country. And with them—interest in Eastern cuisine: abundant, bright, attractive.

The mastering of national dishes in everyday life and public dining (primarily Central Asian and Caucasian) became a powerful trend, somewhat devalued only by inappropriate product quality and ignorance of the specific cooking techniques of these peoples. At the same time, it was precisely Eastern cuisine that became synonymous with festive tables in the USSR due to its brightness, sharp taste, and exoticism. And the use of these borrowings in cafeterias allowed departure from the tiresome and bland standard menu.

War

War is not only suffering, battles, pain, and blood. It's also the colossal survival experience of millions of people. And perhaps it was precisely war that made Soviet cuisine what we know today, transforming Mikoyan's partly fantastic experiments into that very real Soviet everyday life.

It was during these years that millions of residents from evacuated regions of the country learned firsthand what Central Asian cuisine was. Not yet very well known in Moscow or Leningrad, it suddenly became close and understandable to family members of Soviet soldiers and officers who found themselves in Tashkent, Samarkand, or Almaty. The symbolic words "plov" and "lagman," "lepeshka" (flatbread) and "uryuk" (dried apricots) would forever enter their speech and remain in postwar memory as symbols of prosperity and satiety.

In those years, the main flow of evacuation from war-affected regions of the USSR fell on Central Asia. The most evacuees—about 1 million people—found refuge in Uzbekistan.

We sometimes wonder: if disaster struck there, could we in Moscow welcome refugees in such a way? After all, beyond purely human assistance with housing and a piece of flatbread, tens of thousands of evacuated orphaned children from occupied territories found their new parents in Central Asia!

In Uzbekistan, even large families adopted Russian, Belarusian, Ukrainian, and Moldovan orphans. Only from Rostov Oblast and Stavropol were students from 30 orphanages evacuated along with staff. Those who lost parents already during combat operations also found refuge among Central Asian residents.

Shaahmed Shamkhamudov (right), his wife Bakhri-opa (centre) and the children whom the couple adopted during the Great Patriotic War.

The Shamakhmudov family became widely known—Tashkent blacksmith Shamakhmudov and his wife adopted 14 children of different nationalities. And there were many such cases. After the war, in Tashkent (according to other sources—in Dushanbe, then Stalinabad), a monument "Mother of Asia" was planned, designed to immortalize the selflessness and generosity of many local women. Unfortunately, by the mid-1950s, due to political changes in the country, this project did not materialize.

But let's return to the culinary theme. The great wartime migration was a powerful factor that influenced both Soviet cuisine and the entire postwar culture and worldview of the people. This process became one of those threads that connected the history of many families with Central Asia and formed collective memory.

Central Asian cuisine forever became one of the elements of this memory. Perhaps it was then that its current popularity was laid in the enormous geographical space where tens of millions of people live. Forget plov! The lepeshka-non (traditional flatbread) is apparently a people's dish throughout the entire territory of the former USSR. At any market from Murmansk to Magadan, you'll find a pavilion where Uzbeks, Tajiks, Kyrgyz bake them in an improvised tandoor (clay oven). Plov, manty (dumplings), lagman (noodle soup), shurpa (meat soup)—this cuisine became an integral element of Soviet culture, part of everyday or festive menus.

Eastern Fairy Tales

Along with many Asian dishes, the Soviet era brought considerable confusion into our culinary arts. Salad "Tashkent" is a vivid example. Today this dish can be found in thousands of Russian restaurants featuring Central Asian cuisine—only in Tashkent itself, they don't even know about it.

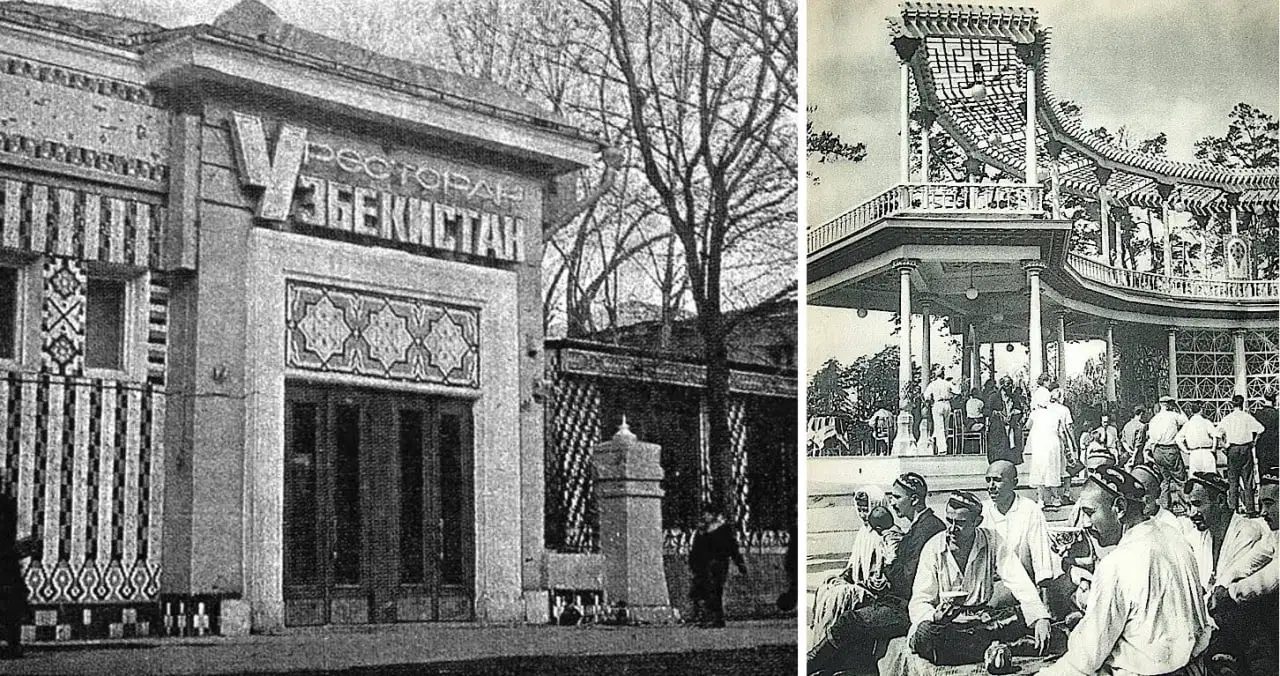

The 1960s were the heyday of Soviet cuisine. It was then that authorities decided to achieve a synthesis not only of cultures of different peoples but even their cuisines. Numerous restaurants of union republics opened in Moscow—"Baku," "Minsk," "Ukraine," "Uzbekistan," "Vilnius," and the Georgian "Aragvi," which had fallen into decline, got new life.

The restaurant "Uzbekistan" in Moscow (1960s) and an Uzbek teahouse at the Exhibition of Achievements of the National Economy (1950s).

Although the menus of these restaurants declared "primordial" dishes of these republics, in reality they were often adapted to averaged all-Soviet tastes. This applies even to republics in the European part of the USSR. And for Asian ones, new dishes were sometimes created, combining some national tradition with capital city cooking views.

For real, what to do if traditional Uzbek cuisine doesn't have salads in the European sense? Yes, there green radish is eaten as an appetizer, dipping it in suzma (strained yogurt). But that's impossible to imagine in a Moscow restaurant. Thus was born such an amazing dish as salad "Tashkent"—a hybrid of traditional Central Asian dish and Olivier salad, fully meeting public dining principles. Julienned boiled meat and radish, fried onions—all drenched in mayonnaise.

It became a model of cafeteria cuisine: simple, technological, doesn't spoil long in the refrigerator, doesn't require particularly quality ingredients (under mayonnaise you can't see anything anyway). As a result, the traditional Uzbek appetizer—sticks of green radish, boiled meat, and suzma—transformed into such a now-classic Soviet salad.

A "Tashkent" salad (photo by Olga and Pavel Syutkin).

Another confusion, this time unintentional, occurred in the USSR with cheburek (a fried meat-filled pastry). This word itself was unknown in Central Russia until the 1950s. The first dictionary to mention it was the pre-war "Explanatory Dictionary" by Dmitry Ushakov. But in just 10-15 years, everything would change. The fact is that the process of international culinary communication occurred independently of the leading role of authorities, sometimes taking completely unexpected forms.

Today chebureki are an extremely widespread dish in Central Asia. But only a few know that it appeared there relatively recently. Being Crimean Tatar in origin, it got there as a result of the postwar deportation of hundreds of thousands of native Crimean residents, took root, and forever entered Central Asian cuisine. And from there, in the 1950s, it gradually penetrated Moscow and Leningrad, where it unexpectedly came to be considered Asian.

Culinary Empire

Multinational Soviet cuisine is not only a beautiful term from the era of developed socialism but also quite a concrete concept in 20th-century culinary arts. Just as pre-revolutionary Russia, the Soviet Union was partly an empire, meaning it absorbed the best of what was in the culture of the peoples comprising it. And this concerned cooking in the most direct sense.

In Soviet times, the entry of national dishes of union republics into the generally accepted diet was very active. Azerbaijani bozbash, Georgian lobio, Central Asian lagman, Moldovan mititei—this was the indispensable assortment of cafeterias in virtually all major cities of the USSR.

By the way, in the 1960s this phenomenon was observed not only in public dining but also in home cooking. Published in 1955 and subsequently mass-produced, the famous "Culinary Arts" gave a kind of "green light" to this process. Moscow publishing houses began releasing in mass circulation various "Dishes of Tatar (Moldovan, Uzbek, Armenian, etc.) Cuisine." Not all of them proved truly useful—many "one-day wonders" appeared, published "for show." But there were also books that still evoke interest, having survived several editions over decades.

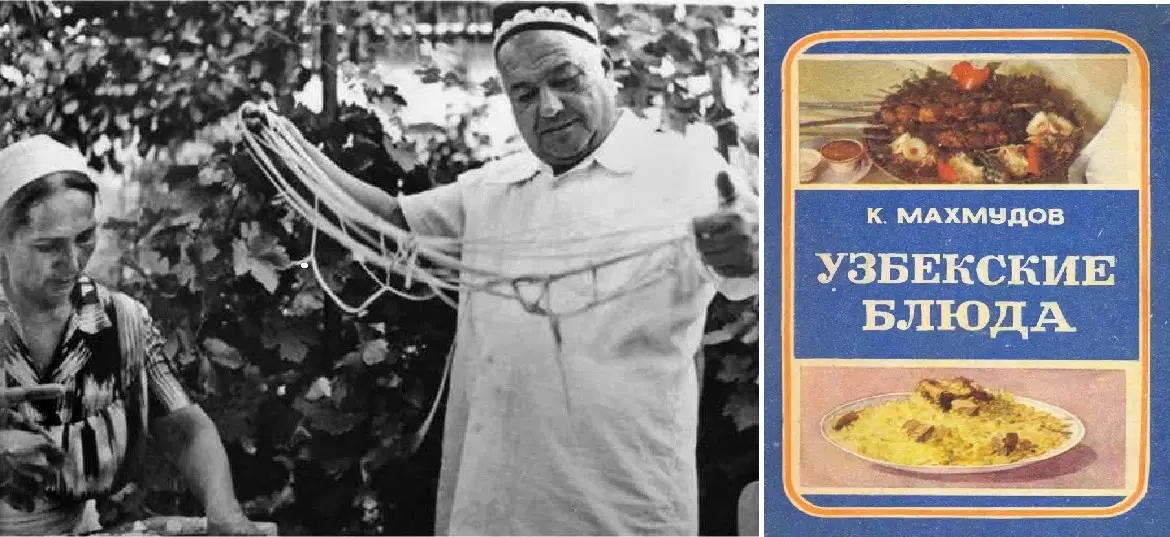

Among them—the works of Karim Makhmudov (1926–1989). An employee of Tashkent State University, associate professor in the philosophy department, he had an amazing hobby parallel to his main work, which made him famous. And so famous that even in modern Uzbekistan he's a cult figure of national gastronomy.

Author of more than two dozen culinary works, he devoted 40 years of his life to this passion. Makhmudov traveled to numerous Uzbek cities and kishlaks, where he recorded ancient recipes, tried to give new sound to ancient cuisine. His first book came out in 1958. Perhaps thanks to his philosophical education and scientific experience, Makhmudov approached national cuisine not simply as a list of recipes and dishes.

His research was much deeper and covered the history of the region, inventory and dishes traditionally used for cooking, dietary and chemical properties of local products, features of cold and heat treatment, regional varieties and differences of cuisines. All these aspects favorably distinguished the works of the Uzbek researcher from the main wave of pseudo-culinary literature, which flourished especially brightly in republican publishing houses.

Take, for example, his book "Plov for Any Taste," published in 1987. It details how to prepare plov in the best traditions of Uzbek cuisine. A total of more than 60 plov recipes are given—with meat and its substitutes (tail fat, horse sausage, chicken, game, fish, egg), plov from wheat and noodles, vermicelli and buckwheat, with peas, mung beans and beans, with quince, stuffed peppers and pumpkin, etc.

In the process of writing this article, I specifically turned to the Russian State Library website. There you can find 12 books by Makhmudov in Russian. Dozens of his books are still in electronic catalogs of Russian online libraries, on culinary portals, on social networks.

Love for Plov is Forever

Like any powerful social cataclysm, perestroika led to enormous population mixing and migration. Hundreds of thousands of Russian-speaking residents of Central Asia began returning to Russia, bringing with them the cuisine of Samarkand, Dushanbe, or Ashgabat familiar to them since childhood. Many representatives of Central Asian peoples, seeking better fortunes, set out for Russia, Ukraine, Belarus.

In Russia itself, many new restaurants and cafes opened. Waves of French, Chinese, Japanese, Mexican gastronomy rolled across the country, replacing each other at the whim of fashion and changing Russian tastes. And only one of their attachments remained constant: plov and manty, samsa and lagman never disappeared from tables in Russia. Moreover, Asian fast food turned into a powerful phenomenon that eclipsed all other cuisines combined.

In Soviet times, Asian and Transcaucasian cuisine always gave the ordinary table a festive tint, as they were connected either with going to a restaurant or with vacationing at the sea. Perhaps it's from those times that this mass demand for southern dishes in Russian public dining comes, because people go there not only to be satisfied but also to get impressions.

According to research conducted this March, in Moscow, Uzbek cuisine steadily occupies fourth place by number of dining establishments, yielding only to Italian, Japanese, and Georgian. And a poll published at the end of 2024 in Rossiyskaya Gazeta showed a convincing result: the leader in delivery in the hot dishes category for all of Russia is plov. Maybe this is the real indicator of how closely our tastes have merged?