ORIGIN OF FLAGS

Art as the Basis of Symbolism

Although today flags look like fabric banners with simplified designs, their predecessors were largely sacred symbols: objects that were more artistic or religious rather than simple symbols of affiliation. Early emblems were more often metal ornaments that were attached to spears.

Warriors went into battle under the protection of various animals representing ancient gods: the Egyptians were patronized by Maahes and Montu, gods of war who appeared in the form of a lion and a falcon, while the Greeks relied on the owl, which symbolized Athena. A similar function of military affiliation was performed by military field standards — vexilla, one of the first mentions of which dates back to the end of the 4th millennium BC and represents a siltstone plate. On the Narmer Palette found in Hierakonpolis, four standard-bearers are depicted carrying animal skins on the tops of vertically held poles.

In Ancient Rome,

military standards held religious significance, symbolizing the presence

of the legion and its protector. It was commonly believed that the power of the army was contained within them,

which is why the banners were kept with special reverence. With the adoption of Christianity, this sacred cult of the standard did not disappear, but on the contrary, was transformed. According to Lactantius, a new symbol appeared to Emperor Constantine before the Battle of the Milvian Bridge, and he replaced the familiar symbols of the Roman gods

with the Christian monogram of Christ. This is how the “labarum” — the cross standard, appeared.

Over time, banners evolved from a simple symbol of belonging into almost iconography and became objects where artistic form merged with the idea of protection and spiritual unity.

From the banner to the coat of arms

The artistic

language in symbols of belonging over time became more formalized and

began to respond to the need for visual "signatures" that could be

distinguished on the battlefield. The fact is that in the Middle Ages, when

a knight lowered his visor, it was difficult for him to recognize, through the slits in his closed helmet, who was friend and who was foe. Moreover, in the bloody chaos

of battle, it was not always possible to identify him as an ally or enemy without distinguishing

marks. This is how family coats of arms appeared.

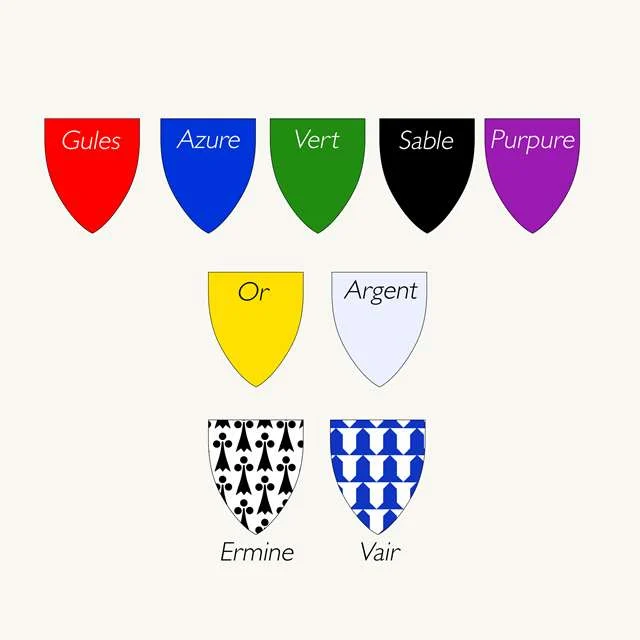

In coats of arms, their own canons were already beginning to be traced, which dictated the composition and color scheme depicted on the heraldic symbol. Thus, European heraldry divided the palette into "dark" colors and "metals," and it was not allowed to place color on color (blue, green, black, red, purple) or metal on metal (gold or yellow, silver or white), since they combined poorly and were unlikely to help knights distinguish friend from foe on the battlefield.

But a coat of arms is not

just about colors. All decorative elements—whether animals, figures, or

stripes—structured the composition and gave it meaning, creating a visual

rhythm. The coat of arms embodied the

ideas of the family, its history and status, using rather modest tools.

Aesthetics and symbolism once again created artistic objects similar to

the sacred banners of the past. And here, you can already see a system of visual

identity, which would later form the basis of national flags: each

detail would retain its symbol and recognizability.

Birth of the flag

It is noteworthy that the word "flag" itself originates from the Dutch language, from the word vlag, which in turn goes back to the Old Dutch "vlac," which translates as "to wave" or "to flutter."

The fact that it was the Dutch language that gave the flag its name is not surprising, since in the 17th century the Netherlands was one of the leading maritime powers and the largest European center of shipbuilding. It was here that ships for the East India Company were built, vessels for the country's navy were constructed, and even other foreign powers received their ships from the local shipyards.

When the Age of Navigation began, the oceans were traversed by many powers—it was difficult to determine, without any identifying marks, whether you faced an enemy or a friend. Political entities increasingly shifted from small principalities and clans to centralized states and acquired their own flags. Thus, at the end of the 16th century, the so-called Prinsenvlag appeared as the flag of the movement against Spain. Unlike the familiar flag of the Netherlands, it had an orange stripe instead of a red one (in honor of the County of Orange). Later, by the middle of the 17th century, the flag with the red stripe became the state flag.

In 1600,

the Dutch already owned about 1,900 sea ships, which was almost five times

more than the English fleet, which at that time numbered 400 ships. The lion's

share of Western European goods was transported by Dutch ships in

the seventeenth century. They controlled not only trade between Spain,

France, England, and the Baltic Sea, but also most of the coastal trade

between French ports. Even French vineyards were privately

owned by the Dutch.

In present-day

Great Britain, King James I in 1606 issued a proclamation according to which all ships of the kingdom

were to fly a flag with two combined crosses — the cross of Saint George

(as a symbol of England) and the cross of Saint Andrew (as a symbol of Scotland).

But flags

served not only an identification role; at times they became signal

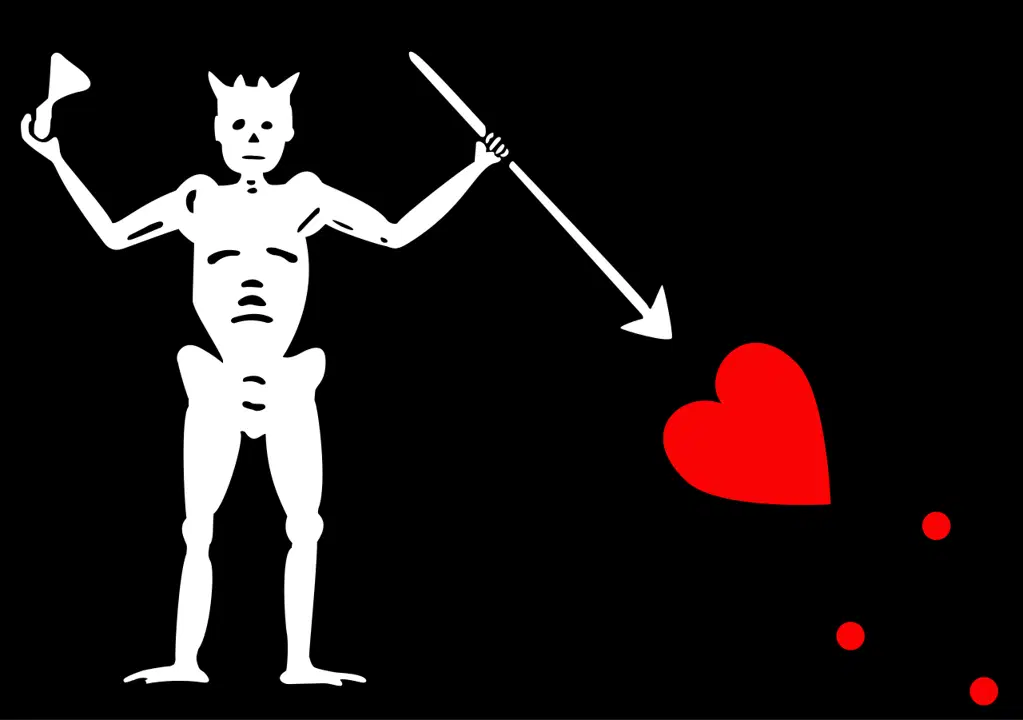

markers. Traditionally associated with death and danger, the color black was widely used by pirates. Corsairs of the 17th–18th centuries did not limit themselves to a black background, but decorated

their flags with skulls, bones, hourglasses, and weapons to inspire fear and

demonstrate their ruthlessness. So, at sea, flags were not only a sign

of belonging, but also a visual language of threat and power.

If the coat of arms symbolized the status of a family, then the flag became a sign of an entire state. It was these early national flags of the Age of Sail that ultimately established the visual logic according to which flags would be created in the future, striving to imbue meaning and recognizability into every detail of the cloth.

Evolution of artistic styles

With the development of national flags, there is a gradual transition to laconicism and geometry. Symmetry, contrast, clear division into fields and stripes become essential tools for the artist shaping national visual identity.

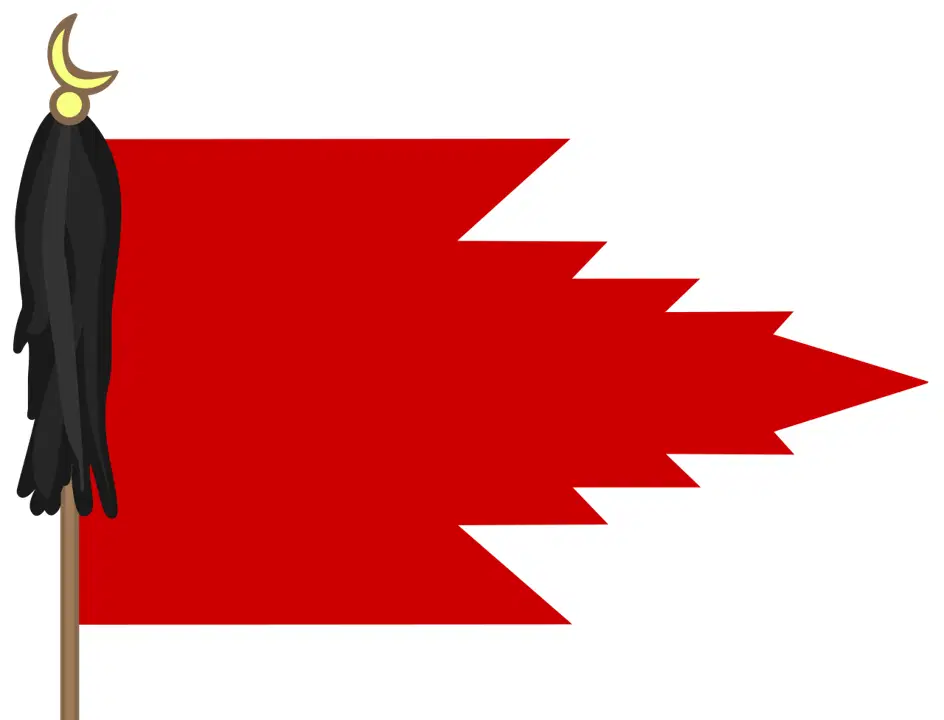

But while the coats of arms of European rulers could be found on shields and castle gates, the symbols of the great conqueror from Samarkand, Amir Timur, were minted on coins and seals. One of the main emblems of the Timurid state—the so-called "Timur's sign"—is three identical circles arranged in the shape of an equilateral triangle. One of the first to describe this symbol was the Spanish ambassador Ruy González de Clavijo. According to the Spanish ambassador, these circles represented the three parts of the world over which the monarch wished to establish his rule. Another interpretation was that this sign reflected Timur's title—Sahib-Qiran, which was translated as "lord of three auspicious planets."

Even less is known about the flags. In historical miniatures and chronicles, red standards with golden crescents often appear, sometimes decorated with horse tails. The period of the Indian campaign was marked by a black banner with a silver dragon, and before the expedition to China, the dragon changed its color and became golden.

Three circles, the "Tamga of Timur," could also have been part of his flag symbolism. In the famous Catalan Atlas of the 14th century, a banner with three circles is mentioned, which could very well have belonged to the Timurid Empire.

FLAGS IN MODERN HISTORY

Flags of the countries of Central Asia

Before the beginning of the Soviet era, each state in the territory of Central Asia had its own banners. Thus, the Bukhara, Kokand, and Khiva Khanates had banners with crescents, inscriptions in Persian and Arabic, and the colors and decorations reflected dynastic traditions. Most often, the flag was not a symbol of the state, but rather a military standard that accompanied the ruler during campaigns and celebrations.

With the formation of the Soviet Union, the khanate symbols were replaced by the laconic flag of the Uzbek SSR, where red symbolized the revolution, blue — water and sky, and white — cotton. And, of course, the flag of the union republic featured the sickle, the hammer, and the star.

After gaining independence, Uzbekistan adopted a new national flag, where the colors also had meaning. Blue remained a symbol of the sky and water, while white became a symbol of light, harmony, and purity. Green represented fertility and the bounty of nature, and red — vital energy.

The crescent on the flag does not carry religious significance — it is a symbol of new life, and the twelve stars are a symbol of a cloudless sky.

But the flag of Uzbekistan is not at all about stripes and a crescent with stars. It is about historical memory, geography, cultural heritage, and new hopes. Adopted in November 1991, it carries echoes of ancient traditions, becoming a bridge between the past and the future: from the depths of the history of ancient khanates to the modern independent state. The colors become not only the palette of the country—deserts, rivers, valleys, and mountains—but also of its mentality: openness, perseverance, and faith in renewal. Today, it is a symbol of an era when the country is building its own identity, expressing it with simple but recognizable signs.

At the same time, the visual identity of the Republic of Karakalpakstan was being formed, which acquired its own flag in 1992. Its palette echoes the Uzbek tricolor, but is full of regional meanings. Blue represents the key element for the Aral Sea region—water; yellow symbolizes the natural realities, as most of Karakalpakstan is desert; green points to the renewal of nature, and the five oldest cities of Karakalpakstan are reflected in the form of five stars on the flag.

Based on this, from the khanate standards to the modern flag, a line of visual identity can be traced throughout the history of our land, where every detail is significant and carries its own meaning.

The influence of Eastern ornamentation

Central Asian flags are not just state symbols, but a true visual cultural code. For example, the blue color on the flag of Uzbekistan not only represents the sky and water, but also historical continuity, referring us to the times of Amir Timur. On the flag of Kazakhstan, blue goes back to the heritage of the Turkic-Mongol tradition and the historical connection with the Blue Horde. The ornament placed at the hoist represents Eastern motifs that have been used for centuries in textiles and decorative arts.

But the rethinking of flags with symbols characteristic of Central Asian peoples is still happening today. At the end of 2023, Kyrgyzstan updated its national flag, replacing the wavy sun rays, which previously resembled a sunflower, with straight ones, and in the tyundyuk the number of rods was increased. These changes are meant to give the symbol more clarity and further emphasize the connection with national tradition.

Ornaments and history have shaped the unique aesthetics of the flag, where patterns and colors helped interpret the meaning of the cloth not as an element for a military parade or office decor, but as a sacred object, where every detail reflects the identity and spirituality of the people.

Modernism and the Digital Age

Digitalization and globalization have allowed the flag to go beyond the boundaries of a physical cloth. Today, it is part of national branding, appearing on websites and in social media profile descriptions, in presentations and mobile applications. Broken down into red, blue, green, and white, it has now become a signature style that is easily recognizable both on a vast billboard and on the small screen of a smartphone.

In digital format, the flag of Uzbekistan still retains its brightness and the distinctness of all its symbols down to the last star. Likewise, the flags of other countries, converted to digital format, help promote national identity without losing their recognizability.

The artist as the creator of a symbol

The creator of the flag becomes a mediator between the culture, the past, and the future of the country. By creating the predecessor of the UN flag, Donal McLaughlin proposed a universal language of peace by depicting olive branches on a blue background, understandable to everyone.

We spoke with Tursunali Karimovich Kuziyev, an artist, photographer, educator, Honored Art Worker, and academician, and he shared with us his vision of the flag.

For him, it is simultaneously a political tool, a work of art, and a source of emotions. The flag is equal to an expression of power, ideology, and unity, but at the same time remains a visual masterpiece, capable through form, color, and even fabric to convey the idea of the Motherland, to evoke a sense of pride, hope, protection, and aesthetic pleasure.

The development of a flag, according to Tursunali Karimovich, requires strict adherence to artistic principles, which include conciseness of form, expressiveness of color, and harmony of proportions, because the main tasks of a symbol are to be understandable, universal, and emotionally powerful. And from an artistic point of view, a symbol is a work in which two colors are important, and in exceptional cases—three.

The national flag of my Homeland — Uzbekistan — is especially dear to me. Firstly, it was adopted on my 40th birthday: and now for the 34th time I celebrate this holiday together with my birthday. And for 25 years now, I have been wearing a tie with the colors of our tricolor on holidays. Secondly, with all due respect to the flags of other countries, I believe that our flag is more of a people's flag and less politicized.

Tursunali Karimovich Kuziyev

According to Kuziyev, the flag should live together with the country. A revolution, which our state has faced in the past, a change of regime, or simply a desire to reflect new national ideas can be the reason for changes, because a flag designer is not a craftsman, but an interpreter of the national idea, translating the national idea into the language of visuals.

The future of flags as art

The flag has become a living and dynamic symbol, but its presence in society is changing. Virtual reality sets its own rules of the game — colors are changeable. In practice, this means that officially approved color shades are necessary. For example, in Turkmenistan, the official Pantone colors of the flag were established back in 2017 to preserve a unified style.

And although Uzbekistan has not yet officially approved the digital values of the colors of its flag, there are already versions with Pantone-codeson the internet. The formal establishment of such shades will become an important step towards creating a universal symbol, equally recognizable and aesthetically accurate, both on fabric and on the screen of any device.

The adoption of official digital colors will ensure the stability and consistency of the flag's visual appearance in printing, media, on souvenirs, and in government publications without the risk of distortion or loss of color saturation.

In the years of digitalization and globalization, the flag becomes a link between generations, between tradition and modernity. As a symbol of theMotherland, it is able to speak through form, color, and symbolism louder than any words, preserving national identity in every line and pattern. And unified and precise shades will help the flag maintain artistic and historical unity, making it recognizable not only within the country but also beyond its borders.

The flag has passed through millennia of transformations and reinterpretations, paving its way into the minds and hearts of modern people, proving one simple thing — in the process of self-identification and state-building, symbolism is inherent to humans. And the best tool for expressing symbols is art.

The banknotes used in Central Asian countries are also artistic and political symbols. Read more in our article: